By Matthias Röhrig Assunção.

Piaçaba Beach

Indigenous people, invaders, colonizers and hundreds of thousands of enslaved Africans arrived over the waters of the Guanabara Bay. During the first centuries of colonization, many enslaved Africans were disembarked next to the square then called Largo do Paço. According to some chroniclers, capoeira in Rio de Janeiro was born here, on the former Piaçaba beach, among the slaves for hire, the dockers, the fishermen and sellers of fish and shellfish.

The land next to the beach was occupied by Carmelite monks and became the square of their monastery. The monks, according to the chronicler Vivaldo Coaracy, had a reputation for being “turbulent, trouble-makers, and unruly”, always provoking the intervention of authorities. For example, they did not allow funeral processions to pass in front of their cloister. They would send their slaves with cudgels to break up the cortege.

The capital of de colonial Brazil

The viceroy once complained about the noise coming from the Quitanda, but the black women from the Mina Coast were in possession of their licence issued by the municipal council and managed to remain. In other words, popular groups tried to defend their place in the centre of the city, and the most densely populated space was the Paço Square.

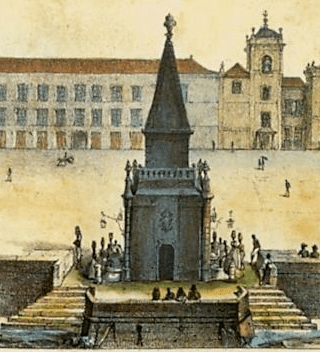

Mestre Valentim, son of a Creole black woman and a Portuguese aristocrat, designed the fountain (chafariz), which provided ships with water from the Carioca river, and was inaugurated in 1770. At the time the chafariz was located next to the quay, as appears in contemporary paintings.

The pillories (Pelourinho) were another monument that embodied colonial power and justice, standing in the middle of the square during the colonial period (it does no longer exist today). With the migration of the Portuguese Court, in 1808, the palace on the square became the official residence of the king and the Portuguese government. The king, however, preferred to live on the Quinta da Boa Vista estate, quieter and more peaceable, and so did the two Brazilian emperors after him.

The Paço Square constituted an important space of sociability for all inhabitants, described by many travellers and chroniclers. The engraving by Friedrich Salathé (1834), based on a watercolour by his friend Johann Jacob Steinmann, depicts the various social groups occupying the square. Among them, two black boys (moleques) engaged in what seems an acrobatic game, which reminds us of some of the movements of capoeira:

To know more:

Vivaldo Coaracy. Memórias da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Belo Horizonte e São Paulo: Itatiaia e EdUSP, 1988.

Antonio Colchete Filho. Praça XV. Projetos do espaço público. Rio de Janeiro: Sete Letras, 2008.

De los Rios Filho, Alfonso Morales. O Rio de Janeiro Imperial. 2 ed., Rio: Topbooks, 2000 (1 ed. 1946).