Augustus Earle's Negroes fighting, Brazils

By Sarah Thomas.

Excerpt adapted from chapter 6, from the book Witnessing Slavery: Art and Travel in the Age of Abolition, by Sarah Thomas, published in 2019, in London, by the Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art for Yale University Press.

Augustus Earle is thought to have been the first professional freelance artist to tour the globe (Hackforth-Jones, p. 1). Today he is as well-known in Australia as he is in Brazil; in Britain, the country of his birth, his name barely registers. The son of an American Tory portrait painter, he exhibited a precocious talent for painting from an early age. He was only thirteen when he first exhibited at the prestigious Royal Academy in London, where he became a regular exhibitor until the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, when travel to Europe was re-opened. He toured extensively across the Mediterranean and the United States, before arriving in Rio de Janeiro in 1820 at the age of 27: he stayed and travelled in South America for the next four years. Invited to Calcutta by Britain’s Governor General Lord Amherst, Earle’s passage was waylaid as his leaky ship discharged him in Tristan da Cunha, a remote volcanic island in the South Atlantic sea.

Marooned for eight months, he was picked up by a ship heading to Australia. After several productive years there and in New Zealand, Earle’s restless spirit saw him employed as a draughtsman on the now famous voyage of the Beagle in 1831, during which time he forged a close and constructive friendship with Charles Darwin. Having suffered from ill health (‘asthma and debility’) for many years, Earle died alone back in London at the age of forty-six.

Work by Augustus Early, in the collection of the National Library of Australia: Augustus Earle, Solitude – Tristan D’Acunha, – Watching the horizon, 1824, watercolour on paper; National Library of Australia (Rex Nan Kivell Collection NK12/3)

During most of his worldly perambulations Earle was in constant search of novel and informative subjects for the British art market. When financial necessity demanded, he sought portrait commissions from members of colonial aristocracies, notably those in Rio de Janeiro and Sydney. The gregarious and well-heeled artist was capable of mingling with, and securing patronage from, the upper echelons of colonial societies, yet he was drawn by temperament and the exigencies of the market towards recording the daily life of the marginalised: enslaved and indigenous people, convicts (transported to Australia from Britain), and the working classes. While he rarely portrayed such figures in oil paint, they are a prominent feature of many of his watercolours. Earle’s eye for parody and humour links him directly to the British satirical tradition—exemplified by such artists as Rowlandson, Gillray and Cruikshank—whose drawings and prints were hugely popular in the period.

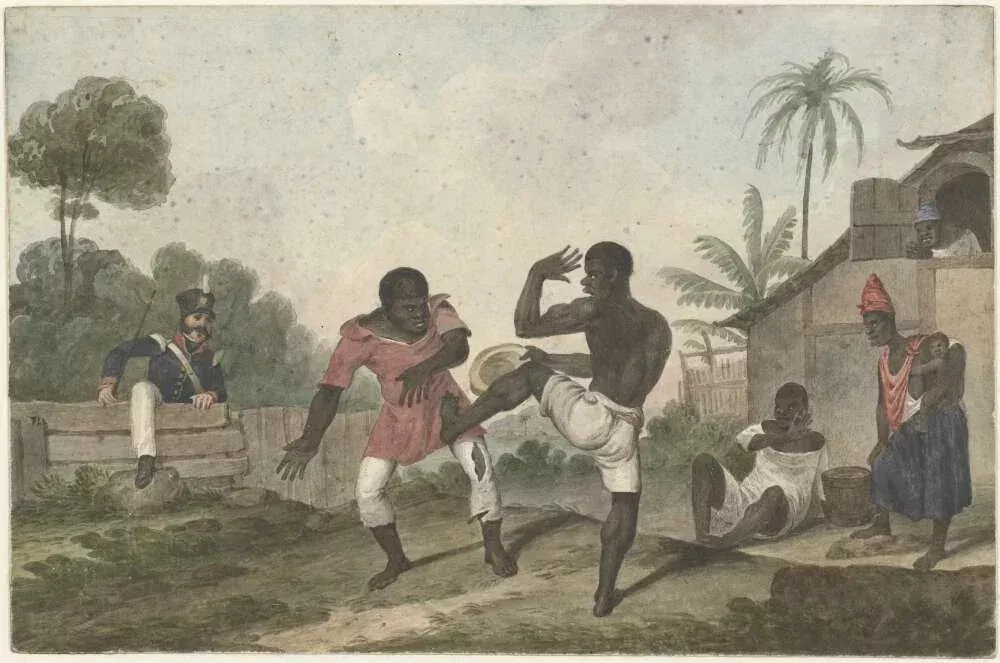

Negroes fighting, Brazils c. 1822 is one of around twenty Brazilian watercolours by Earle held by the National Library of Australia. In the early decades of the nineteenth century, Rio de Janeiro had the largest urban population of enslaved people in the Americas; by 1821 they totalled some 36,000, a figure that had more than doubled since the arrival of the Portuguese royal court in 1808 (Karasch, pp. 61-62). Enslaved Africans had come to dominate the city to an unprecedented extent, and were a ubiquitous and highly visible aspect of Cariocan life, performing a wide diversity of jobs and engaging in a broad range of social and religious activities. Earle was more likely to gently deride his European counterparts than the enslaved he saw in Brazil.

Nevertheless, as a resident of Rio de Janeiro, Earle was surely aware that in this period capoeira was being targeted by police authorities as a form of antisocial behaviour – along with disorderly conduct, vagrancy and public drunkenness (Assunção 2003, p. 165). As this painting suggests, capoeiras were widely revered by the enslaved; yet their superb fighting skills, physical agility and high level of organisation did little to endear them to the police. Some were thought to be involved in plotting insurrection, and they were closely surveilled. While the authorities were largely ineffective at policing such gatherings, the existence of such tensions lends Earle’s watercolour a somewhat darker subtext (Karasch, p. 243). However, true to form, Earle delights in satirising the physical disparity between the puny symbol of authority and his burly charges. He emphasises the stylised elements of capoeira rather than its lethal potential, thus going some way to reassure the European spectator that law and order prevailed at all levels of Cariocan society.

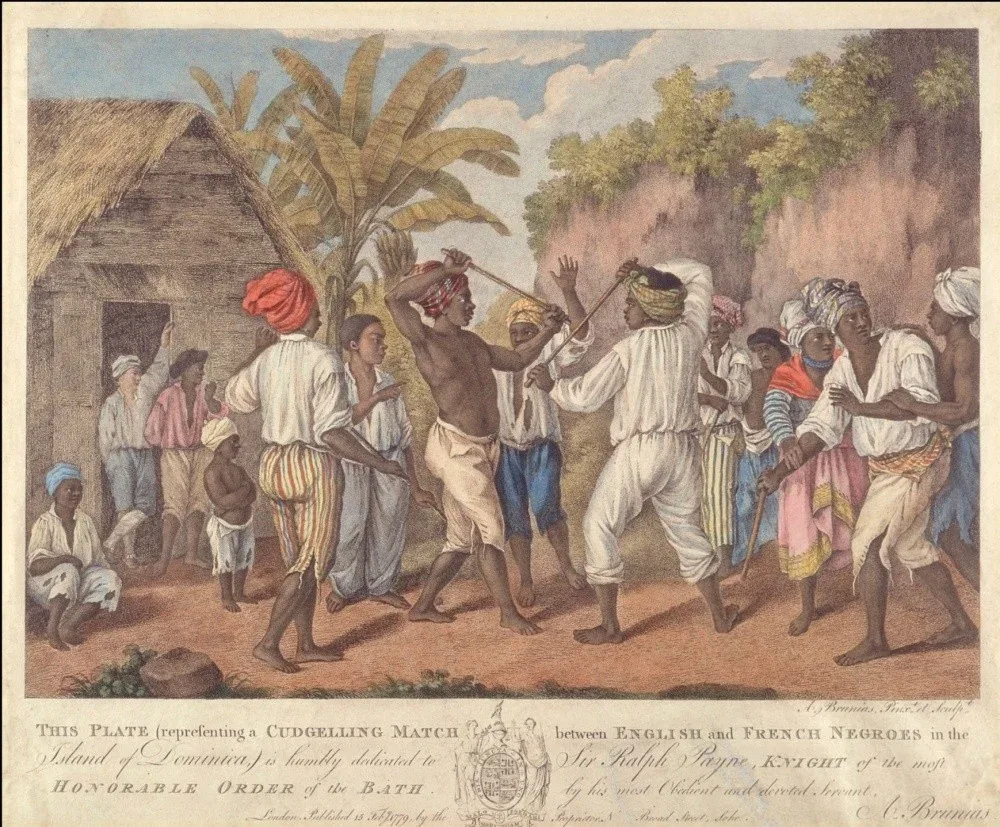

A comparison of this watercolour with a slightly earlier engraving by another itinerant artist working elsewhere in the service of empire is instructive: Agostino Brunias’s A Cudgelling Match between English and French Negroes in the Island of Dominica (1779).

The setting was the Campo de Santana, where another contemporary artist, Frenchman Jean-Baptist Debret, had portrayed the enslaved being publicly flogged. Yet what Earle turns his attention to here is not the spectacle of punishment, but to unabashed revelry. In 1808 a British merchant had described the Campo de Santana thus:

theatre of revelry and din. Here was the native of Mosambique, and Quilumana, of Cabinda, Luanda, Benguela, and Angola. . . . You might see the cheeks of an athlete of Angola ready to crack under the exertion of producing a hideous sound from a calabash, while another performer dealt blows so thick and heavy on his kettledrum, that only the impervious nature of a bullock’s hide could resist them. . . . every looker-on participated in the sibylline spirit which animated the dancers and musicians; the welkin rang with the wild enthusiasm of the negro clans. (Robertson, p. 166-67).

In Earle’s painting, a central male dancer’s raised arms might indeed suggest the influence of the Iberian fandango, to accord with the work’s title, although it is more likely that the dance was the batuque, a forerunner of the modern samba, which was widely practiced by the enslaved in Brazil from the seventeenth century onwards. Scholars have highlighted the extraordinary transcultural hybridity of such Afro-Brazilian dances, particularly if one considers the original Moorish and gypsy influences on the fandango (Chasteen, pp. 33-35).

The overt sexuality of such dances was not the only aspect that troubled European spectators: so too was the sense of rebellion that such gatherings signified. From at least 1817 the city authorities had begun restricting the large congregation of enslaved people as they were seen as disturbing the public order, and by the time Earle was living in Rio de Janeiro batuque dancers were frequently being arrested. (Assunção 2005, p. 40; pp. 75–90). Metropolitan and plantocratic fears of insurrection lay behind the increased curtailment of such gatherings, particularly after the 1804 triumph of Haiti’s enslaved. Little wonder then, almost out of sight on the far right, the artist included the quietly reassuring figure of a soldier overseeing the festivities, his long sword clearly visible. In acknowledging that it was necessary pictorially to defuse the potential threat contained in his image, Earle also included an unaccompanied European woman and her small child. Such figures function as markers of social cohesion, recognisable symbols of an apparently harmonious multi-racial society whose natural hierarchies are under no threat. The presence of the soldier is a subtle reminder that what appear to be scenes of unabashed communal joy are in fact underpinned by anxious surveillance. Earle reminds us of enslavement’s coercive and violent underpinnings. His tendency to fill his compositions with an array of what might be considered extraneous detail was not only a sign of empirical diligence, but also a means of persuading viewers of his authority as an eyewitness.

Dra. Sarah Thomas is Senior Lecturer in the School of Historical Studies at Birkbeck, University of London. Her book, Witnessing Slavery: Art and Travel in the Age of Abolition was published in 2019 by the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. She has published widely on slavery and visual culture, and the art history and museology of the British empire. She is completing a new book called Chattel: Art, Slavery and the British Collector, 1768-1833.

https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9781913107055/witnessing-slavery/

Other References:

Assunção, Matthias Röhrig. Capoeira: A History of an Afro-Brazilian Martial Art (London: Routledge, 2005).

Assunção, Matthias Röhrig. ‘From Slave to Popular Culture: The Formation of Afro-Brazilian Art Forms in Nineteenth-Century Bahia and Rio de Janeiro’, Iberoamericana, Nueva época, vol. 3, No. 12 (Dec 2003), pp. 159-176.

Chasteen, J.C. ‘The Prehistory of Samba: Carnival Dancing in Rio De Janeiro, 1840-1917, Journal of Latin American Studies 28, no. 1 (1996).

Hackforth-Jones, Jocelyn. Augustus Earle: Travel Artist (National Library of Australia, 1980).

Karasch, Mary C. Slave Life in Rio de Janeiro, 1808–1850 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987).

Robertson, John and William Parish. Letters on Paraguay, 3 vols. (London: John Murray, 1839, 2nd edtion).