By Filipe Amado.

Today we know that the history of capoeira is not restricted to Rio de Janeiro and Bahia. There is evidence in many cities of the intense activity of capoeiras in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. New research is emerging on the subject, even though much remains to be researched and discovered.

São Paulo is one of those places with fertile ground for research into the history of capoeira, and with few works on the subject (CUNHA 2011 and CAVALHEIRO 2017). At the same time, black culture, and especially capoeira in the post-abolition period, is a topic that needs more research, as if there were a hiatus between the great repression at the beginning of the Republic and the development of the Bahian model of capoeira. Based on these concerns, and on the evidence of capoeira in São Paulo not related to the Bahian model (the case of tiririca, which will be explored in another article), I decided to research capoeira here in the first half of the 20th century, and developed this theme in my master’s thesis.

To discuss capoeira in São Paulo in the early decades of the 20th century, it is important to understand that there was a tradition of capoeiragem in the city among slaves, freedmen and even the elite at the Largo São Francisco Law School that goes back as far as the 19th century.

An elite society, mirroring European values, established itself and despised the black presence that stubbornly sprouted in the squares and streets of the city. Emblematic is the removal of the church Nossa Senhora do Rosário dos Homens Pretos, which was located on rua XVth of November (now largo Antônio Prado) and, in addition to Catholic services, was a place for meetings and African religious and cultural practices. There were a cemetery and black dwellings around the church, situated right in the heart of the city. Its change of address to Largo Paissandu (current location) in 1904 was part of a hygienist policy that aimed to expel the black population from the centre, open squares and avenues to improve the flow of people and cars and bring “progress” to São Paulo (BRITTO, 1986 and SECO, 2008)

This is the tone taken by newspapers in the first two decades of the 20th century, when discussing the black population and its practices, including cases of capoeira, which crop up in the crime pages and portray capoeiras as transgressive bandits, but which also reveal their playful side, the formation of groups along the lines of the cariocan gangs.

- Oh Iron! I've never seen so much steel!

According to an article in Correio Paulistano on 26/11/1907, which reproduces an record of the Municipal Council of São Paulo from 1907, since the beginning of that year, judges in the capital had passed sentence in 673 cases of capoeira, vagrancy, gambling, use of prohibited weapons, and crimes against labour. These are all crimes related to the marginalised population. They are forms of repression, control and exclusion of their activities that did not fit into the society that was being formed in São Paulo at the beginning of the 20th century.

The expression “Oh Iron! I have never seen so much steel” may be attributed to the capoeiras of the early 20th century in São Paulo, it is found in some articles referring to capoeira. On May 28th 1900, the newspaper Correio Paulistano presented in a few lines in the Daily Life Column, thogether with other news of assaults and robberies, the news that “Candido Elias Gonçalves, who boasts to be the best capoeira of this land, yesterday night made a nice scene by making fall the minors who were watching the scene in the palace garden, shouting Oh iron, I’ve never seen so much steel!”

Like Candido Elias, there were hundreds of capoeiras scattered throughout São Paulo, resolving conflicts, fighting and resisting arrest, training and enjoying playful moments with capoeira. Yes, there are many newspaper reports of capoeira as a game, which shows that it always had and never lost that characteristic. However, since newspapers only report crimes or matters involving the police, violence is a constant feature of capoeira reports, and often the games ended in fights:

In Rua Vergueiro, the black Alfredo Eugênio, 22 years old, resident at alameda Ribeiro da Silva n. 57, was playing capoeira yesterday at 2 o’clock in the afternoon with several companions. One of these fellows, exasperated after having been taken down by Alfredo with a rasteira, shook him with a knife on the right side of his lower jaw. The aggressor then fled and the victim was treated at the Central Police Station.” (Correio Paulistano, 02/07/1913. Bolded emphasis added).

These early 20th-century capoeiras used jackknives, clubs and canes, weapons inherited from imperial capoeira, as well as classic blows and kicks such as headbutts, rasteiras and rabo-de-arraias. They fought for territory and space in the city, and at all times resisted the imposed model of civilisation.

Formation of the groups

In 06/12/1903, the Correio Paulistano published the following note, reproduced here in full:

CAPOEIRA – Yesterday, the pimp Maria Luiza, had a discussion at her house, on Senador Feijó street, with Carolina Vieira and Guilhermina da Silva. After a long exchange of insulting words, Maria Luiza began to play capoeira. On that occasion, however, a police officer arrested Maria Luiza, by order of Dr. Pedro Arbues Junior, 2nd policde chief..” (Bolded emphasis added)

Though fewer in number, the newspapers reveal instances of women playing capoeira and participating in the world of bravery and rogueness on the streets of São Paulo. Maria Luiza is not the only one to use capoeira in conflicts, and like the men, she had a marginalised profession, as a pimp in a brothel. The capoeiras were therefore cartmen, bricklayers, prostitutes, painters, porters, among other professions where the black population found possibilities of survival, but who carried with them a tradition coming from the 19th century of autonomy and freedom in the urban environment.

The news of 15/01/1900 in the Estado de São Paulo reveals a bit more about the organisation in groups:

It is well known, by all who pass by the Carmo floodplain, on Sundays, from noon onwards, the very original spectacle offered by the unemployed of Vinte e Cinco de Março and Santa Rosa streets, of some combats fought with stones on the gasometer embankment. … the Brás authorities managed to find out that the unemployed from Santa Rosa street have three parties formed, which dispute with three others from Vinte e Cinco de Março street, each with a different flag and their respective chiefs, who are vagabonds trained in the game of the sling, capoeira and jacketknives, who impose themselves on their companions and subordinates by force and brutality, which they show in their onslaughts on the floodplain. (Bolded emphasis added)

Here we clearly see the formation of capoeira groups, with hierarchies, since there are chiefs, territorialities linked to the streets and symbols that identify them, such as flags. These are equivalent characteristics to the 19th century carioca gangs and although they do not receive this name here, they have a clear similarity. More than that, they are various associated groupings, since there are three from rua Vinte e Cinco de Março, which is on one side of the Tamanduateí River, and three from rua Santa Rosa, on the other side, that is, they are groups with territorialities, in many ways similar to the federations of maltas Nagoas and Guaimuns.

From this and other news, we have evidence that the Várzea do Carmo region was a place of dispute between maltas or capoeira groups, probably a border zone. Here it is worth noting that malta is na old Portuguese term which is no longer used in the Republic and therefore the newspapers do not qualify the groups as such anymore.

The news of 08/02/14 in the Estado de São Paulo shows a grouping of capoeiras, and not without reason in a region historically occupied by blacks:

We are asked to call the attention of the police on a group of individuals who give free capoeira lessons every afternoon until late at night on Conselheiro Carrão Street, on the stretch between the corner of Ruy Barbosa and Treze de Maio. Families are not allowed to pass through there, because the attitude of such people is too audacious and disrespectful. (Bolded emphasis added)

If the regularity of the meeting “every afternoon” in Bexiga shows how capoeira was an everyday practice in São Paulo, the fact that capoeira was taught there reveals a possible way of transmitting capoeira in groups, along the lines of the maltas from Rio de Janeiro.

Who sees him so fat

doesn’t know what a capoeira,

what a good whipping goat,

what a good whore to beat.

Confirming what they say,

let Washington Luiz say so…”

The caricature of a capoeira, published in 12/02/1926. The humorous newspaper O Sacy jokes at the end of the caption about the suspicion, which existed at the time, that President Washington Luiz himself was a capoeira.

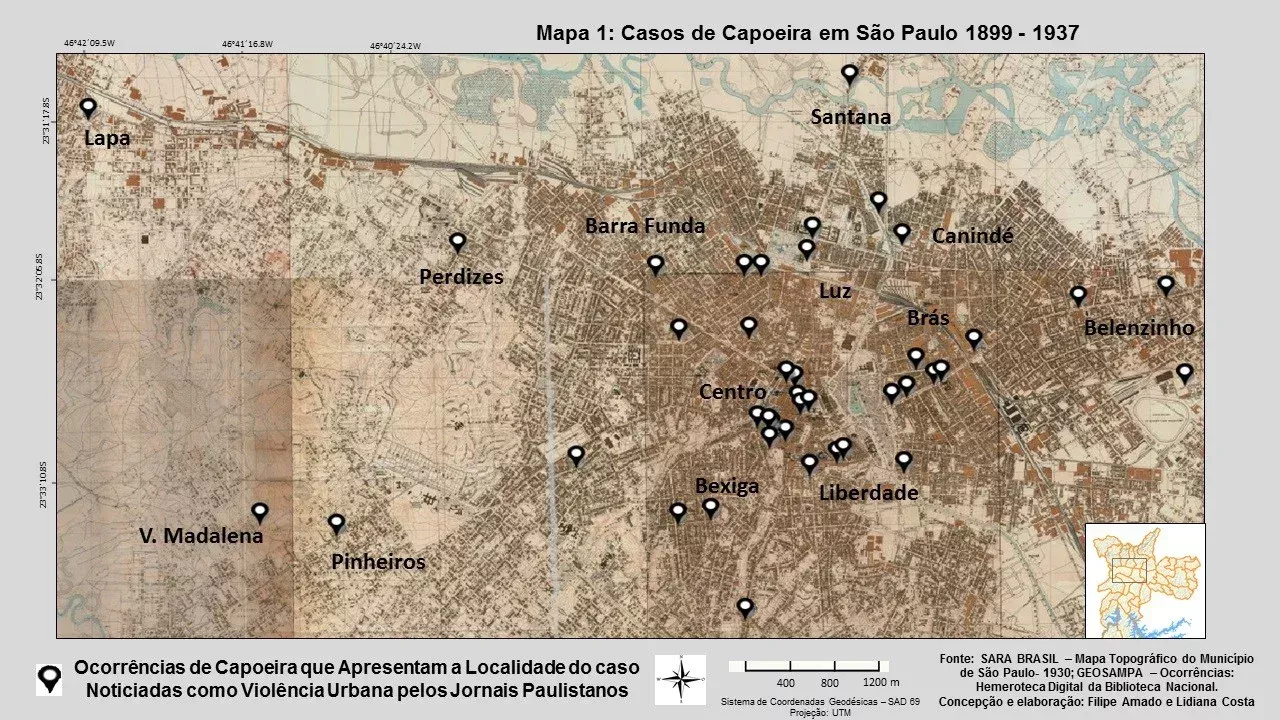

The capoeira map

From the map we can see that most cases occur in the centre and adjoining neighborhoods, made up mainly of the black population, by immigrants and having a higher demographic concentration. Even so, there are reports of capoeira in more distant and sparsely populated neighborhoods, such as Lapa, Vila Madalena and Pinheiros, where in our research we found traces of black communities.

The newspapers in São Paulo often present racial-ethnic traits of those accused of capoeiragem, and these descriptions, almost always imbued with explicit racism, show that the vast majority were black. Not a single white capoeirista in the papers was mentioned. While this cannot be dismissed out of hand, everything leads us to believe that, unlike capoeira in Rio de Janeiro at the end of the Empire, where the presence of whites and immigrants was massive, this was not the case with capoeira in São Paulo in the early decades of the 20th century. In support of this hypothesis, one must take into account the massive discrimination and segregation that existed during that period, and which left capoeira restricted to black communities, at least during the first two decades of the 20th century.

The São Paulo elite, however, also devised its own projects for capoeira, and while the first two decades of the 20th century saw newspaper reports of capoeira as urban violence, by the third decade the tone and focus changed significantly. In keeping with a nationwide movement, the São Paulo newspapers would elevate capoeira to the status of a national symbol, and the art would end up performing in the São Paulo fighting ring to prove its martial efficiency. But that will be the subject of another article.

References:

AMADO, Filipe. Abre a Roda Minha Gente que o Batuque é Diferente, tiririca, capoeira e samba em São Paulo, 1900-1970. Dissertação de mestrado, Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros (IEB) USP, 2021.

BRITTO, Iêda Marques. Samba na cidade de São Paulo (1990 – 1930): Um Exercício de Resistência Cultural. São Paulo: FFLCH/USP, 1986.

CAVALHEIRO, Carlos Carvalho. Notas para a História da Capoeira em Sorocaba. Editora Crearte, Sorocaba, 2017.

CUNHA, Pedro Figueiredo Alves da. Capoeiras e valentões na história de São Paulo (1830-1930). Dissertação (Mestrado em História Social) – Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2011.

SECO, Lincon (org.) São Paulo Espaço e História, LCTE Editora, São Paulo, 2008.

Filipe Amado is historian (FFLCH USP) with a master’s degree in Brazilian studies (IEB USP).

Newspapers consulted:

Correio Paulistano: 28 de maio de 1900

Correio Paulistano: 26 de novembro de 1907

Correio Paulistano: 6 de dezembro de 1903

Correio Paulistano, 2 de julho de 1913

Estado de São Paulo: 15 de janeiro de 1900.

Estado de São Paulo, 8 de fevereiro de 1914

O Sacy, 12 de fevereiro de 1926