By Mauricio Acuña

Mestre Pastinha: the written mischiefs of a capoeira-author uses excerpts from the chapter “Quando as letras fazem, mizerer: práticas de escrita na cidade gingada,” from the doctoral thesis by Mauricio Acuña (2017).

…it’s just that I’m not really an author who died, but a dead author…”

Machado de Assis, The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas.

One of Mestre Pastinha’s most important roles in capoeira throughout the 20th century, which is relatively unknown, is of a writer dedicated to thinking and sharing reflections on capoeira. There are several texts that haven’t yet received the attention they deserve, which I’m going to share here.

As a strategy to enter the circle of Pastinha’s writings, I suggest beginning by following in the footsteps of another Afro-Brazilian master from the peripheries, the writer Machado de Assis. In The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas, the writer creates a character from Rio de Janeiro’s elite who affirms his status as posthumous author, thus defining the originality and power of his place of writing. Brás Cubas is not a writer who, having died, writes from beyond the grave, but a dead man who has decided to start writing. Based on this original inversion, we can think of Mestre Pastinha not as an author who uses capoeira as a theme or style, but rather as a capoeira-author, and therefore as a capoeira mestre who writes. However, the situation of our capoeira-author is not so simple when we read what he wrote and how his writings were read and considered.

The main problem is about the right to write and to public recognition of those who write under the conditions of structural racism and the social formation of slavery in Brazil.1 It is, therefore, a question that has existed since at least the time of Pastinha’s birth in 1889, a year after the abolition of slavery and shortly after the publication of Machado de Assis’ book. The reflection I’m proposing is on the history of Pastinha’s writings and the ways in which they have been received and interpreted over time, including the headbutts, handstands, gingas and rasteiras that have since circled out. Each of these gestures inspires the titles of the following sections.

1 I refer to contemporary reflections on racism using these terms (Almeida, 2019; Sodré, 2023), which also include Suely Carneiro and the “device of raciality” (2023), as well as the recent work of Ynaê Lopes dos Santos, Racismo Brasileiro (2022).

Cabeçada (headbutt)

In that year, the ethnographer Edison Carneiro and the writer Jorge Amado advocated the creation of a federation of capoeiristas, after the exhibition of Samuel Querido de Deus, Aberrê, Bugaia, Onça Preta, Barbosa, Zepelim, Juvenal, Polu and Ricardo at the Second Afro-Brazilian Congress in Salvador.

Mestre Pastinha was also a creative sower of capoeira songs, recorded both in his writings and by the Afro-Bahian ethnographer Waldeloir Rêgo in his pioneering work Capoeira Angola: Ensaio Sócio-etnográfico (1968). The composed and improvised quatrains gained notoriety with their recording on disc in the 1960s, where we hear the mestre’s ‘ABC’ telling stories about himself and capoeira. It is also important to highlighting that ‘Pastinha has already been to Africa’, as he was chosen to represent Brazil at the First World Festival of Black Arts in Dakar (FESMAN). Besides the well-known disc, the capoeira-author would record compositions in manuscripts and notebooks, such as the one he prepared in the 1960s at the request of Mestre João Grande. Carefully kept by his disciple for almost fifty years, Pastinha’s Improviso was published in 2013 by pioneering capoeira researchers, Frede Abreu, and Greg Downey.

But Pastinha continued to pursue writing as a way of spreading his ideas among capoeiristas and beyond, as was the case with texts given to musicologist Emília Biancardi in 1963. Biancardi was the founder of the folklore group Viva Bahia, recognized for taking Afro-Brazilian cultural manifestations to national and international stages. At the beginning of this century, this collection of Pastinha’s writings took shape in the bilingual edition (Portuguese and English) by Frede Abreu and Greg Downey, Mestre Pastinha: How I think? Despised?, whose title evokes questions about himself and those who judge him.

Bananeira (handstand)

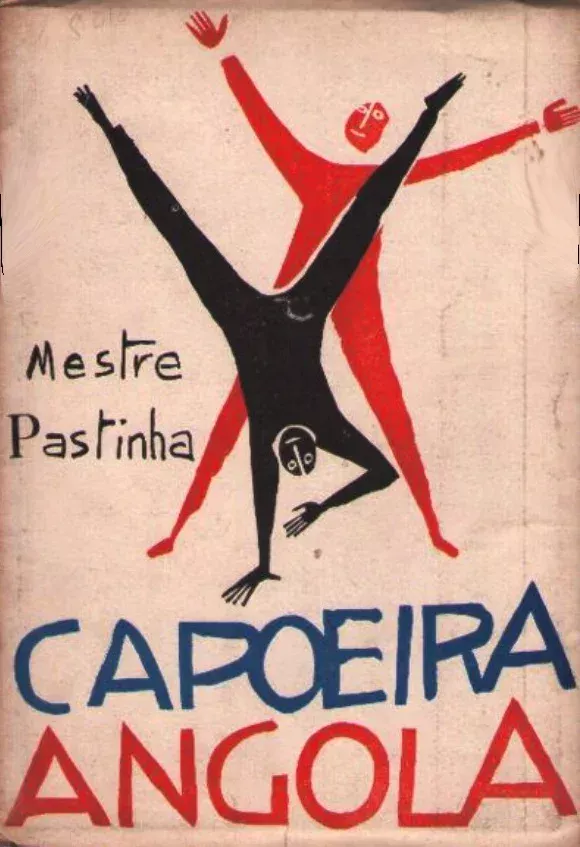

This inverted position, with the feet up and balancing on the hands, allows the capoeirista to attack or ‘move in any direction’ (Pastinha, 1964) and, in our case, it helps us to think about the pause before the attack that represented the publication of the famous book Capoeira Angola, printed at the Escola Gráfica Nossa Senhora do Loreto in 1964 and republished in 1988, on the centenary of the abolition of slavery.

The final composition of the book resulted in a text that underwent extensive editing, possibly by the doctor José Benito Colmenero and even by Jorge Amado himself, according to the statements of Pastinha’s partner, Maria Romélia Costa Oliveira, Dona Nice, who accompanied him on visits to Amado’s house in Rio Vermelho neighborhood to show him the drafts of his book (Acuña, 2017: 203). The editorial intervention of university-educated figures such as Colmenero and Amado in texts by people with primary education, such as Mestre Pastinha, was not uncommon. The example of the great writer Maria Carolina de Jesus, whose book Quarto de despejo dates from the same period, illustrates this practice. This poisonous situation raises the question of authorship and conformity to the ‘cultured norm’, which, seen from an Afro-Atlantic perspective, invites us to think less in Portuguese and more in Pretuguese, as Lélia Gonzalez teaches us.2.

2 See, for example, the dossier about the author, where in the introduction, Osmundo Pinho explains that “pretuguese” is “the subversion of the Portuguese language carried out by the ladino blacks, who, when learning the language of Camões, transformed it into something else, in the slave quarters and streets…” (2019: 42).

However, it’s important to emphasize that Pastinha’s relationship with Jorge Amado was characterized by friendship and the writer’s support of the master’s creations, as well as encouragement to Pastinha’s involvement in Bahia’s literate scene. Pastinha also became a fictional character for the writer.

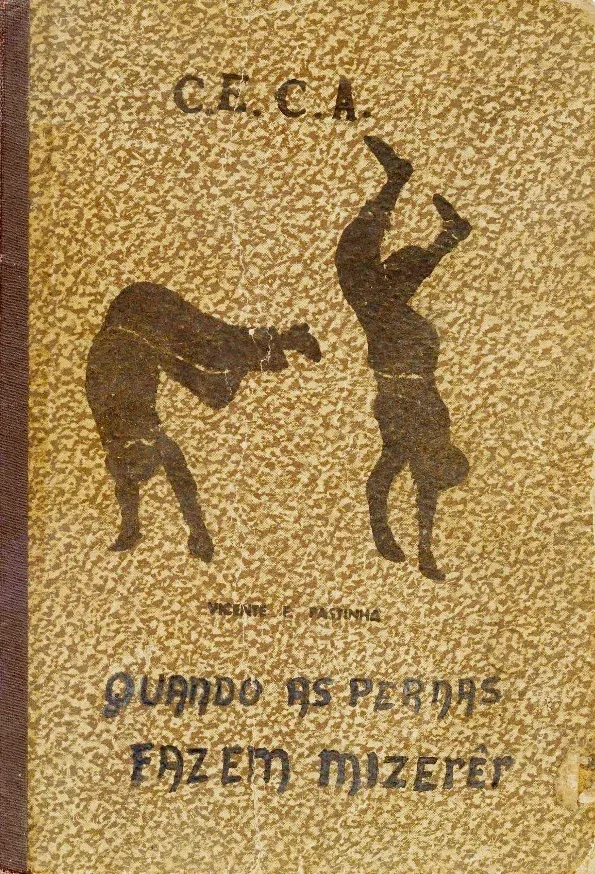

Ginga

With smooth movements, of great flexibility and all the extraordinary malice of capoeira (Pastinha, 1964), ginga is the perfect movement to symbolize Mestre Pastinha’s greatest effort as a capoeira writer. This would have taken place between 1958 and 1962, when he dedicated himself to writing the manuscripts for a book that would never be published. The Bahian press recorded his involvement with this project. In 1959, for example, he was described as ‘the author of several notebooks with teachings, annotations and drawings’3.

Two years later, his name appeared for the first time associated with a book project entitled Metafísica e Prática da Capoeira de Angola (Metaphysics and Practice of Capoeira de Angola), which would be illustrated by Carybé and include texts by Wilson Lins. At the time, however, Pastinha’s authorship was not recognized and the book was attributed to Lins (Acuña, 2017: 200). Shortly afterwards, the book Capoeira Angola was published and the Metaphysics and Practice of Capoeira de Angola project, which had been announced in the press, simply disappeared from the horizon. It is possible that both the mestre’s health conditions and the political and cultural situation in Bahia and Brazil under a dictatorial regime contributed to the manuscript not being published.

After Pastinha’s death in 1981, new clues about the manuscript emerged, for example during the thirtieth day mass organized by Dona Nice, Jorge Amado and Wilson Lins. Lins stated at the time that he planned to publish a book co-authored with Pastinha, entitled Metafísica e Prática da Capoeira (Metaphysics and Practice of Capoeira), but the project was never realized. Several years passed before Pastinha’s words, kept by Carybé and Wilson Lins, were handed over to Mestre Decânio (Ângelo Decânio Filho). More than forty years passed before the manuscripts were first published in 1997 under the title A Herança de Pastinha, (Pastinha’s Heritage).

3 Souza, José de. Capoeiristas bahianos – Mestre Pastinha. Boletim da casa da Bahia, Rio de Janeiro, abril-maio 1959.

Mestre Decânio’s affectionate publication transcribes the original text and adds comments to further develop the mestre’s thoughts and create reading keys. In the same period, Decânio published a second edition with Pastinha’s original handwriting and his drawings.

A few years later, the “caderno-albo” was finally scanned and given a digital version, with global dissemination via the internet, where it sails freely. With this move, the manuscripts have become one of the main sources for understanding Pastinha’s thinking and teachings.

Rasteira (sweeping kick)

We close with the rasteira, a gesture of dragging your foot in front of your opponent, which could well refer to the uncertain fate of Pastinha’s manuscripts and the analyses of his writings. The format of the manuscripts is not consensual in terms of their organization or length and, since their publication, the differences between the writing style (vocabulary, sentence structure, punctuation etc.) and the form of argumentation (tone, purpose, readers, linguistic resources etc.) have become more evident, especially when compared to the 1964 book Capoeira Angola. On the other hand, since the 1990s, various researchers, mestres and mestras have been learning from Pastinha’s knowledge and defending his recognition as a philosopher of capoeira (Decânio, 1996; Araújo, 2015; Assunção, 2005).

The bad news is that such an important body of Mestre Pastinha’s creations, which disappeared until the 1990s, remains inaccessible. Although it circulates on the internet in digital form, the material base of the words and drawings that Mestre Pastinha bequeathed is not available. This situation imposes a limitation on capoeiristas, researchers and anyone interested in having direct contact with the mestre’s words. It is very important to make a collective effort to widen access to the manuscripts and give them a careful and generous home, where the debate and historical memory of one of the greatest masters of capoeira and Afro-Brazilian cultures can continue to nourish bodies, letters and imaginations.

There are several institutions capable of housing the mestre’s manuscript, such as the Afro-Brazilian Museum, the Bahian Academy of Letters, the Brazilian Capoeira Angola Association, the Jorge Amado House Foundation, among others. What is certain is that Mestre Pastinha’s authorial legacy is fundamental to understanding his vision of ancestral Afro-descendant art and its history.

Although the manuscript took decades to be published, Pastinha is a pioneer among capoeira masters in the use of writing as a means of disseminating ideas and has his own style of summoning memory and arguing. The publication of his texts put him at the forefront of a trend that was only consolidated at the end of the 20th century, when other capoeira mestres began to have their writings published.3. In this way, Pastinha’s writings shed light on less-discussed aspects of his life, revealing a generous author who, rooted in capoeira, thinks, improvises and cultivates historical, aesthetic, political, pedagogical and philosophical forms of knowledge.

And Mestre Pastinha, capoeira-author and sower of words, may still have left more writings to be discovered. So, alongside the many songs that today chant ‘viva Pastinha!’, we can smile and add: ‘leia Pastinha,’ which with its written mischiefs invites, as in the litany, ‘man, boy, and woman’ and many more to the rodas of the present and future challenges. Iê!

3 Among the few precedents, the books by Mestre Acordeon (1986), Nestor Capoeira (1992), and the manuscripts by Mestre Noronha, published in 1993, stand out. As analyzed by Matthias Assunção, Noronha’s manuscripts, “constituem um texto extremamente denso e uma mina de informações inéditas” (2014: 92).

References

Acuña, Mauricio. A ginga da nação: intelectuais na capoeira e capoeiristas intelectuais. São Paulo, Alameda, 2015.

______. Maestrias de Mestre Pastinha: um intelectual da cidade gingada. Tese de doutorado, Departamento de Antropologia da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo, 2017.

______. “Mestre Pastinha.” In: Gomes, Flávio dos Santos, Jaime Lauriano e Lilia Moritz Schwarcz. Enciclopédia negra: biografias afro-brasileiras. São Paulo, Cia das Letras, 2022.

______. Poéticas e performances de imaginações afro-atlânticas: O primeiro festival mundial de artes negras. Tese de Doutorado, Departamento de Espanhol e Português, Universidade de Princeton, 2021.

______. “Escritos de geração: Jorge Amado e Edison Carneiro na roda da capoeira.” Revista Trilhos, v. 2, n. 1, junho, 2021.

Araújo, Rosângela. É preta, kalunga: a capoeira angola como prática política entre os angoleiros baianos (anos 80-90). Rio de Janeiro, MC&G, 2015.

Almeida, Silvio. Racismo Estrutural. São Paulo: Sueli Carneiro; Pólen, 2019.

Assunção, Matthias Röhrig. Capoeira: the History of an Afro-Brazilian Martial Art. New York: Routledge, 2005.

______. “Uma visão de dentro da vadiação baiana: os manuscritos do Mestre Noronha e o seu significado para a história da capoeira.” Revista África(s), v. 1, n. 2, jul./dez. 2014.

Carneiro, Sueli. Dispositivo de racialidade: a construção do outro como não ser como fundamento do ser. Rio de Janeiro, Zahar, 2023.

Decânio, Filho, Ângelo. A herança de Mestre Pastinha. A metafísica da capoeira – comentários de textos selecionados do mestre. Salvador: Coleção São Salomão, 1996.

Pastinha, Mestre. Capoeira Angola. Salvador, Escola Gráfica N.S. de Loreto, 1964.

______. Os manuscritos de Mestre Pastinha. Salvador, S.ed; s.d.

______. Centro Esportivo de Capoeira Angola. Salvador, edição do autor, 1963.

______. Como eu penso? Dispeitados? Salvador, Instituto Jair Moura, 2013.

Pinho, Osmundo. “Introduction” (Dossier: el pensamiento de Lélia Gonzalez, un legado y un horizonte). Lasa Forum, v. 50, p. 41-43, 2019.

Santos, Ynaê Lopes dos. Racismo Brasileiro: uma história da formação do país. São Paulo, Todavia, 2022.

Sodré, Muniz. O fascismo da cor. Rio de Janeiro, Vozes, 2023.

Thanks Mauricio and capoeirahistory team for the amazing article!