Prestigious gifts in the era of the trade in enslaved Africans

By Ana Lucia Araujo.

The exchange of gifts has been part of social protocol since at least antiquity. Gifts were central instruments in diplomatic exchanges during the Middle Ages and into the early modern era, on several occasions helping to seal agreements and initiate business deals. That heads of state receive gifts from foreign nations is nothing new. For example, the collections of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in the United States include dozens of works of art and artefacts given to him by heads of state from all over the world, including Africa.

In Brazil, exchanges of gifts have historically been associated with corruption. Every Brazilian knows how exchanges of gifts influence political life and business. After all, offering gifts to politicians, civil servants, executives and employees of private companies has always been a thinly veiled way of trying to gain an advantage. Gift exchanges have also been a feature of corruption scandals. The most recent of these was the case of the former Brazilian president, the fascist Jair Bolsonaro, and the then first lady Michelle Bolsonaro, who received jewellery and luxury watches as gifts from the Saudi Arabian government and then illegally sold several of these million-dollar gifts.

What few people know is that during the era of the Atlantic trade in enslaved Africans, European and American slave traders also offered gifts to African rulers, officials and traders when they arrived on African shores, even before starting the process of buying enslaved Africans to transport them to the Americas.

Most often, the gifts were exactly the same items transported aboard slave ships to the coasts of Africa, where they were used as currency to purchase enslaved people. These items included fabrics, alcohol, cowrie shells, iron bars and manufactured items such as rifles, knives, clothing, pans and cutlery. In this context, these articles were used as a form of tribute, given to the various African agents established along the coast to initiate trade.

Over the years, European traders learnt the very specific tastes of African rulers and agents and were thus able to provide exclusive items to African traders to please them and, in return, obtain the best captives within the shortest possible time. In this context, gifts could also be conceived as bribes, because by offering them to African agents, ship captains and European merchants sought to obtain advantageous conditions in the trade of human beings. For example, expensive fabrics and manufactured items such as clothes, hats and metal items were reserved for rulers and agents who held higher positions. In addition, as part of these exchanges, African traders also offered men, women and especially children as gifts to European traders and rulers.

Prestigious gifts made of valuable materials remained essential items in the Atlantic trade in enslaved Africans until the mid-19th century. But, like the gifts given to Bolsonaro, there are controversial stories behind some of these presents, which today form part of European and American museum collections.

In June 1775, the French slave ship Le Montyon, followed by the corvette L’Hirondelle, sailed from the French port of La Rochelle to the coast of Loango, north of the Congo River in west-central Africa, to trade in the ports of Cabinda and Malembo, in the region of present-day Angola. The captives bought by these captains would then be transported on the two ships to Saint-Domingue-Saint Domingo, to work on the plantations of the richest French colony in the Americas. Daniel Garesché, a very wealthy shipowner, slave trader and future mayor of La Rochelle, then the second busiest French port for the slave trade, equipped and owned the two ships.

After arriving in Malembo, a port that was part of the Kingdom of Kakongo, the captains of the La Rochelle were invited to go and buy captives in Cabinda, a port located a few kilometres north of Malembo and which was part of the territory of the Kingdom of Ngoyo. However, when the captain of the L’Hirondelle and some of his crew arrived in Cabinda, they were attacked by the captains of French ships from Bordeaux and Le Havre, who threatened, assaulted and stole some of the cargo they had transported to buy captives in Cabinda. Fortunately for the La Rochelle traffickers, they managed to save themselves after Andriz Pukuta, the commercial agent (mfuka) of the king of Ngoyo, offered them shelter in his house.

Two years after this incident, Garesché again sent Le Montyon from La Rochelle to buy captives on the Loango coast. This time, the captain of his ship carried a ceremonial sword made of silver to be presented as a gift to Andriz Pukuta, the Cabinda commercial agent who two years earlier had saved the French slavers’ skins. The gift was a way of thanking him for having protected the captain and crew of La Rochelle two years earlier. The sturdy silver ceremonial sword is an impressive object. Measuring over 50 centimetres, the shape of the sword is similar to that of the bimpaba (singular kimpaba), ─ ceremonial swords among the Vili people of the Loango kingdom, the Kotchi of the Kakongo kingdom and the Woyo of the Ngoyo kingdom on the Loango coast

Kimpaba at the Musée du Nouveau Monde de La Rochelle. Photo by Ana Lucia Araujo, 2022.

On the tip of the sword is a dedication engraved and written in French with the words ‘Andriz Macaye Mafouque le juste de Cabinde,’ praising the mfuka as a just man. Also engraved on the tip of the sword are garlands of flowers, decorative elements very common in 18th century French watercolours and silver objects. In addition, a cross has been carved into the tip of the sword and the false blade contains a curious series of geometric elements with triangles and semicircles.

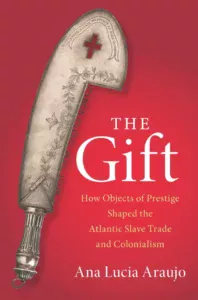

My book The Gift follows the tortuous journey of this silver sword from La Rochelle to Cabinda, and from Cabinda to Abomé, in the Bay of Benin and back to France, where it is now on display at the Musée du Nouveau Monde in La Rochelle. I explore how and why the silver sword was created, who created it, and why it was important to French traders and agents and rulers in the Bay of Loango. I also examine the cultural, religious and artistic meanings of this sword for the rulers and craftsmen of Dahomey, from where it was looted during the Second Franco-Dahomean War in 1892. I argue that the silver sword provides a complex and nuanced framework for better understanding the history of the Atlantic trade in enslaved Africans on the Loango coast, where the Kingdom of Ngoyo and the port of Cabinda were located, as well as in French slave-trading ports such as La Rochelle.

I believe that this type of study offers an opportunity to highlight the importance of material culture and to elucidate the meanings of exchanges of gifts and objects of prestige during the era of the trade in enslaved Africans. The movement of this silver sword also sheds light on the connections between the Loango coast and the Bay of Benin, two regions that have been studied separately by scholars of African slavery and trafficking. As well as examining the complex trajectory of this silver sword, the book places this object in dialogue with other similar objects made in Europe and Africa. In doing so, this research aims to contribute to complicating discussions about the looting and circulation of African objects and requests for the repatriation of African cultural heritage addressed to European and American museums.

Ana Lucia Araujo is a historian and full professor of History at Howard University in Washington DC, USA and a member of the scientific committee of UNESCO’s Route of Enslaved People project. She is the author of several books, including Reparations for Slavery and the Slave Trade: A Transnational and Comparative History (Bloomsbury, 2023), The Gift: How Objects of Prestige Shaped the Atlantic Slave Trade and Colonialism (Cambridge University Press, 2024) and Humans in Shackles: An Atlantic History of Slavery (University of Chicago Press, 2024).

Further reading:

Araujo, Ana Lucia. Humans in Shackles: An Atlantic History of Slavery. University of Chicago Press, 2024.

Araujo, Ana Lucia. The Gift: How Objects of Prestige Shaped the Atlantic Slave Trade and Colonialism. Cambridge University Press, 2024.

Beaujean, Gaëlle. L’art de la cour d’Abomey : Le sens des objets. Paris: Presses du Réel, 2019.

Ferreira, Roquinaldo. “Central Africa and the Atlantic World.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History, 30 October 2019 https://oxfordre.com/africanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-53.

Fromont, Cécile. The Art of Conversion: Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Silva, Daniel Domingues da. The Atlantic Slave Trade from West Central Africa, 1780–1867. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2017.