By Marcos Leitão de Almeida.

In her post for this blog, historian Mariana Candido rightly stated that there is a lack of archaeological evidence for southern Angola. We should add that linguistic evidence is also missing. As Africanists since the 1960s have stressed incessantly, there is not one without the other in the constitution of a truly local history on the African continent. And the truth is that, despite the advances in historiography and archaeology since independence, in southern Angola, as far as historical linguistics and archaeology are concerned, everything has yet to be done.

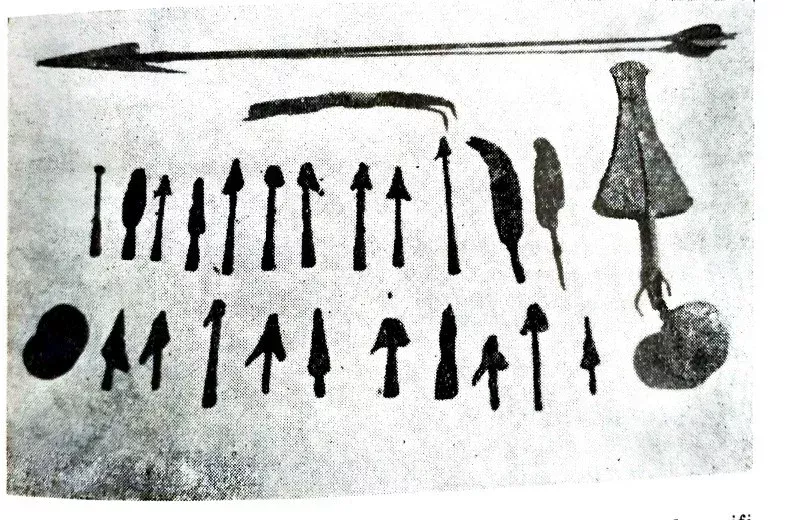

Well, almost everything. From an archaeological point of view, since at least the 1950s, archaeological sites documenting the presence of small axes, bifacial tools, chisels and scrapers have been found on the coast (at a site called Baía Farta) and elsewhere in the south of the country. The oldest site dates back 714,000 years and is testimony to the antiquity of human occupation of the region. However, the number of archaeological sites grew more than expected during what Africanists call the “Later Stone Age”, especially when you consider the difficulty and scarcity of research on the subject. Thus, around 8,000 years ago, the profusion of small archaeological sites documented in southern Angola and the Congo suggests that these small groups of people lived by hunting and gathering, a form of subsistence indicated by the spearheads and stone arrows left by time.

Archaeologists have long known this material culture as “Wilton”, which is characteristic of an eclectic form of subsistence that extended from southern Mozambique to southern Angola. Historians, such as Chris Ehret, and archaeologists and linguists, such as James Denbow and Thomas Güldemann, have proposed in their studies that the creators of the Wilton culture spoke languages from the KhoeSan group. This story is crucial in challenging the previous paradigms of conquest and domination in the Bantu expansions, which fascinated the first interpreters of the Bantu-speaking migrations and which still mistakenly inform popular and academic perceptions of the subject today. Today, we know that complex interactions, involving marriage, exchange and trade, formed the basis of the intimate relationships between KhoeSan-speaking populations and Bantu-speaking immigrants when the latter arrived in the region around the last millennium BCE. These interactions continued for centuries until, during the first millennium of the Common Era, in a period of great social change, the Bantu-speaking populations ended up distancing themselves from these pioneer populations and displacing them towards the south, certainly also through violence.

Little is known about material cultures during the first millennium of the Common Era in southern Angola. Ceramics, associated with iron and stone utensils or found in contexts with rock art, have been discovered in Benguela and Baía Farta. However, the precise dating of these items and the determination of the lifestyle of their users – whether they were hunters, herders or metalworkers – remain uncertain. As has been known for decades in Africanist studies, this is where archaeological studies can benefit from linguistic studies, as the latter offer hypotheses of migrations, settlements and lexically reconstructable items that archaeologists can use to guide and enrich their research, hypotheses and conclusions.

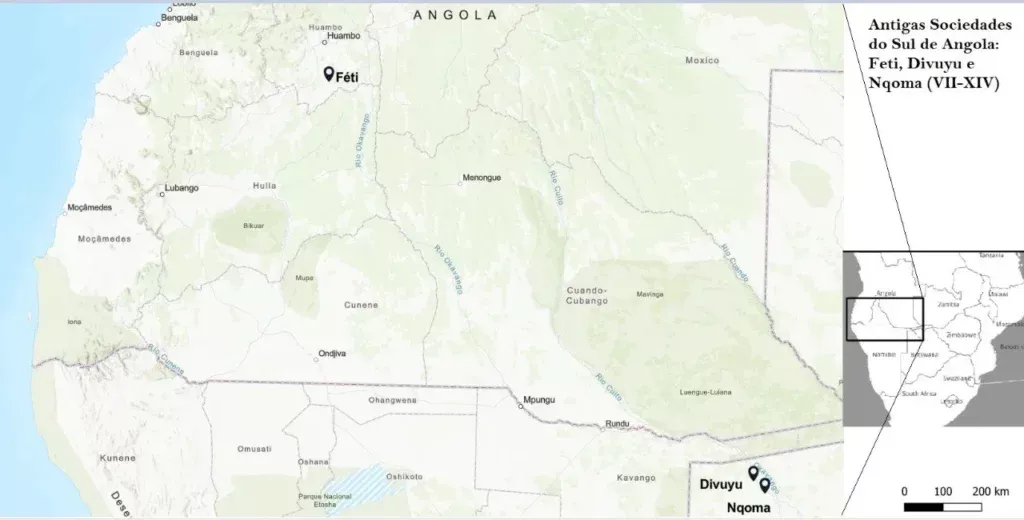

It is therefore impossible to talk about the social complexity of Angolan antiquity without mentioning the appearance of three important centers in the second half of the first millennium CE. First, we have Divuyu, the oldest archaeological site in southern West-Central Africa where two of the region’s most important social innovations first appear: the formation of large villages and the domestication of cattle. Here, in the Okavango delta, immigrants of still unknown origins established a complex society where shepherds and farmers, associated with masters of the art of forging iron, did not produce the metal, but traded it along with ivory, animal skins and shells from the Atlantic. This trade indicates long-distance routes in Central Africa before the year 1000. Notably, another site near Divuyu, Nqoma, had trade links with the Indian Ocean, evidenced by the possible exchange of ivory and specularite for sea cowries and glass beads.

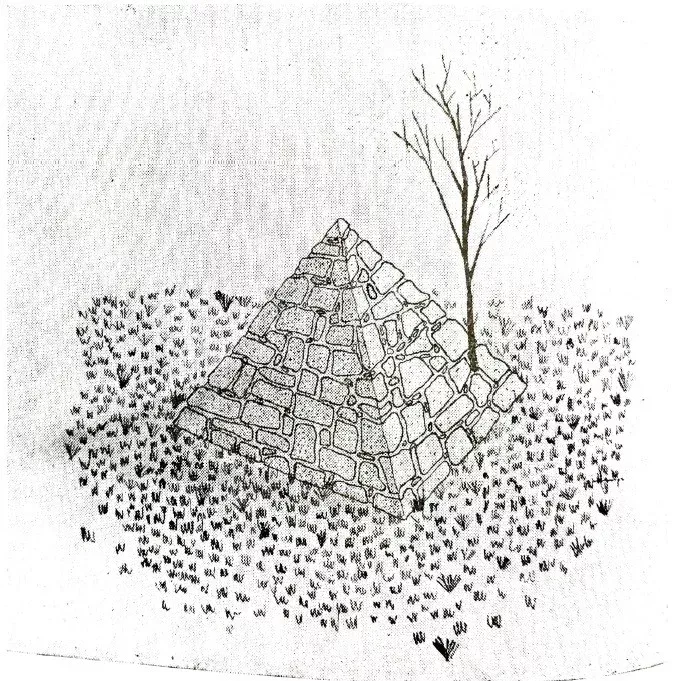

Lastly, the kingdom of Feti is the most important archaeological center in southern Angola at the end of the first millennium CE. Emerging between 700/900 CE until its virtual extinction around 1400, Féti was once compared to the great Zimbabwe. Local traditions recognize Féti as the first large state on the Huambo plateau, where it is likely that its inhabitants spoke a language from the Proto-Kunene group – although more research is needed to confirm this hypothesis (these same traditions suggest that the site’s name derives from efeti, “genesis” in contemporary Umbundu. However, whether the derivation is a folk etymology or not is something that only in-depth research can answer). Therefore, the clumsy exploration of the site by Júlio Diamantino de Moura in the 1940s and the subsequent flooding of the area by a hydroelectric plant caused an irreparable loss to Angola’s archaeological heritage. At the site, Moura discovered a stone pyramid, circular structures and an elevation covered in black earth containing animal and human bones. The findings indicate a huge settlement, similar to a political capital, funerary practices and possible rituals. It was possibly the capital of a political state, i.e. a “kingdom”. As such, signs of combat and violence were part of its daily life, suggested by the external trenches, defensive structures and spears found. Although much remains to be discovered, this evidence indicates a society with social inequality, complex organization of work and violent interactions with neighbors.

Pyramid of Feti. Image from the article “Uma História Entre Lendas”, by Julio Diamantino de Moura, Boletim do Instituto de Angola, nº 64 (1957), p. 55‑75.

So we still know very little about the ancient history of southern Angola. But from the little we do know, we can glimpse a dense history, no less complex than more famous African societies such as the kingdom of Congo, Zimbabwe and the Upemba depression, to name but a few in Central Africa. How can we find out more? To begin with, linguistic research capable of refining the linguistic classification proposed by Jan Vansina (and which he himself took from a classic study published a few years before his book) must be carried out to shed light on the historical contingencies of southern Angola between 500 and 1500. With a new refined classification, it is possible to reconstruct vocabularies pertinent to the domains of social history, including those pertaining to forms of combat, types of violence and kinds of warfare. This has not yet been done for this region. In any case, the archaeological remains collected so far are important and are both a challenging and exciting start to the ancient history of the African continent.

Challenging because recent historiography has unfortunately focused on historical periods after the 16th century or, in English-speaking contexts, after the 19th century. This trend has relegated ancient history to the periphery of historical studies, a phenomenon that several historians have drawn attention to because of its similarity to the colonial approaches of the early 20th century. In Brazil, the decline in interest in Africanist studies prior to the 19th century is also a trend, with thematic symposia dedicated to this period being absorbed by those focused on more recent centuries. As we celebrate 20 years of the law no. 10.639 (which requires the study of African history in Brazilian schools), this reinforces the importance of recognizing the ancient history of Africa as an integral and vital part of the discipline, and not just as an “exotic spice” condensed into introductions of books focusing on more recent periods.

In this challenging context, however, there are still pockets of resilience and growth that also come from the Global South. Notable examples include the excavations in Ilé-Ifé and Oyo-Ile, Nigeria, under the coordination of Adisa Ogunfolakan and Akin Ogundiran, the work at the National Archaeological Museum of Benguela (MNAB), led by Maria Helena Benjamim, and the formation of the working group “Archaeology of Africa and its Diasporas” by the Brazilian Archaeological Society. These initiatives are essential for breaking down the fictitious divisions among “prehistory” and “history” and for challenging epistemological approaches that are excessively centered on written documents produced by foreigners.

In southern Angola, most of the research has yet to be done. But for the first time since 1975, there is a movement to form alliances and advance the field of archaeology in the region. Linguistic archaeology, in particular, promises to reveal new layers of understanding about the past. However, we must first recognize that as long as we continue to divide the study of archaeology from the study of history, and in the wake of this division reinvent a “pre” only to split it off from the “history” that we want to tell with the documents in the colonial archives, we will continue to alienate Africa’s distant past from the post-colonial nation-state. As archaeologist Akin Ogundiran rightly said in his opening remarks to the 22nd Congress of the Brazilian Archaeological Society in 2023, to reverse this situation, we need to “employ our eclectic methodology of deep time research to bring indigenous cultures into our history journals.”

Marcos Leitão De Almeida, PhD in African History from Northwestern University and awarded for the best doctoral thesis in 2020, is a professor at the Federal University of Juiz de Fora.

He is currently working on a book about the history of slavery in ancient Central Africa, which will be published in Brazil in 2024.

Bibliography:

CHILDS, Gladwyn Murray. “The Chronology of the Ovimbundu Kingdoms”. The Journal of African History, vol. 11, no. 2 (1970), p. 241‑248.

DE MATOS, Daniela, MARTINS, Ana Cristina, SENNA-MARTINEZ, João Carlos, et al. “Review of Archaeological Research in Angola”. African Archaeological Review, (2021). Available at <https://doi.org/10.1007/s10437-020-09420-8>

DENBOW, James R. “Interactions among Precolonial Foragers, Herders, and Farmers in Southern Africa” in DENBOW, James R. (Ed.). Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. [s.l.]: Oxford University Press, 2017. Disponível em: <https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.71>.

DENBOW, James R. The Archaeology and Ethnography of Central Africa. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

MOURA, Julio Diamantino de. “Uma História Entre Lendas”. Boletim do Instituto de Angola, 1957, p. 55‑75.

VANSINA, Jan. How Societies Are Born: Governance in West Central Africa before 1600. [s.l.]: University of Virginia Press, 2005.