A brief history of kokobalé and its connections to capoeira (part I)

By Carlos “Xiorro” Padilla Caraballo

Where there was slavery there was resistance, struggle and maroonage. In Abya Yala1 (America) part of this maroon manifestation were the warrior traditions. These traditions are part of the knowledge brought by our ancestors from the African continent. Alvin O. Thomson, speaking of this knowledge, says:

Evidently, the Africans (who constituted the vast majority of the enslaved people and the Maroons), came with a stock of thoughts, ideologies, skills, and so on. This formed the basis of their actions, modified by the circumstances of slavery in the new world, and by the new physical and social environments into which they were thrown. Their remarkable flexibility and adaptability, in the face of the nightmare that threatened to destroy them, are attributes of their ancestral heritage, no less important than their own resourcefulness and willpower.”2

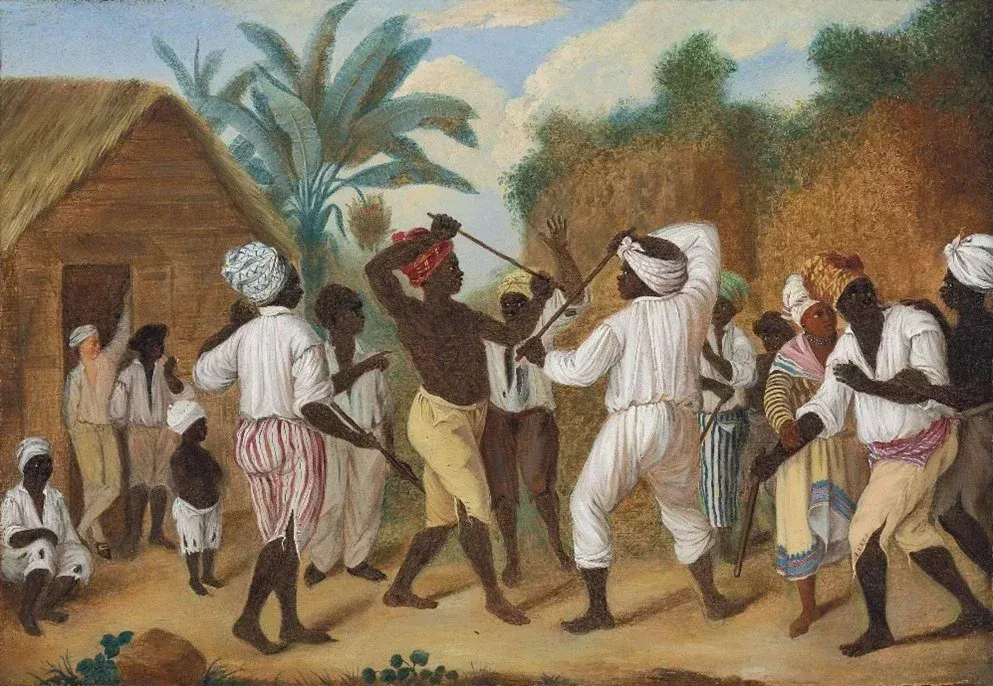

Afro-diasporic warrior traditions are part of this ‘stock of thoughts, ideologies, skills’ that we call ancestral knowledge. Just as Brazil preserved capoeira, the Afro-Brazilian martial art, warrior arts have also been preserved in the Caribbean. The most common of these is stick fighting and/or machete fighting (stickfighting).

1 Abya Yala is an indigenous term of the Guna ethnic group (Panama, Colombia) used to name their ancestral lands. At the II Continental Summit of Indigenous Peoples and Nationalities in 1977, this name was proposed as a decolonial replacement for the European colonial terms ‘New World’ or ‘America’. This name has been adopted by most indigenous institutions and organisations in rejection of the term America.

2 Alvin Thompson, Huida a la libertad. Fugitivos y cimarrones africanos en el Caribe, (Mexico, DF: Siglo XXI Editores, 2005), 14.

In Borikén3 (Puerto Rico) the stick fight is called kokobalé (also spelled cocobalé)4. This tradition is based on African ancestral knowledge preserved in the Bomba. The Bomba is the oldest Afroboricua (Afro-Puerto Rican) music and dance tradition of our archipelago. In Kokobalé, as in Capoeira, two practitioners perform a ‘game’ within a ‘circle’ formed by the musicians and other participants. This tradition is part of a family of sister traditions that appear in most Caribbean islands and in Abya Yala. Anthropologist and archaeologist Tato Torres explains that:

The common presence of several similar combat dances of clear African origin throughout the Americas suggests that these traditions were also common in Puerto Rico. The so-called ‘cocobalé’, like all other bomba dances, probably took a variety of forms throughout the island. The ‘cocobalé’, according to the available literature and oral descriptions, was probably a Puerto Rican interpretation of this African, Afro-American and Afro-Caribbean tradition.”5

3 In this paper I will use Borikén, Boricua and Afro-Boricua instead of Puerto Rico, Puerto Rican and Afro-Puerto Rican to honour the names and the original peoples of our archipelago and to maintain a decolonial logic.

Kokobalé, approx. 1940’s.

Photo by Jack Delano

Next, Edson Teto Azevedo recreated the original image with the help of artificial intelligence.

6 Definition of the Project Kokobalé.

Colonialism and Afro-Borikén traditions

The official history of Borikén has been affected by over 500 years of colonialism. It emphasises narratives that are convenient for the ruling class, as Chinua Achebe of Nigeria said: ‘As long as the Lion does not write his own history, the tales of husbandry will always glorify the hunter’7.

There is little that Puerto Rican history books record of indigenous and African traditions, and of the little that is recorded, most are very convenient accounts for Europeans and the ruling class’8. The history books emphasise a false submission of the enslaved Indians (Tainos), Africans and Creoles (mestizos), hiding the long history of struggles, rebellions and resistance. As Dr. Pedro Lebrón aptly describes:

…much of the historical documentation generated before the 20th century was the product of the judicial and police apparatuses of colonial control and repression. Acts of resistance were framed in such a way that the narratives were oriented towards the preservation of the slave system and white hegemony[…]. In the 21st century in Puerto Rico, the aim is to promote whitening as a social value through the ‘silencing, trivialisation and simplification’ […] of the history of slavery and resistance to it in elementary schools…”8

In short, official history continues to ‘glorify the hunter.’ It is no easy task to write ‘Lion history’ especially to write about a tradition that was passed down orally and existed mostly in secrecy. However, these structural efforts to erase the warrior spirit from our collective consciousness have only been partially successful.

7 Jerome Brooks, “Chinua Achebe, the Art of Fiction, no 139”, The Paris Review, 1994, https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/1720/the-art-of-fiction-no-139-chinua-achebe.

8 P. Lebrón Ortiz, Filosofía del Cimarronaje, (Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico: Educacipon Emergente, 2020), 50-51.

Towards a history of Kokobalé

1. Kokobalé, Bomba and its Kongo-Angolan Roots

Like Capoeira, Kokobalé and Bomba have a strong Kongo-Angolan influence. Linguist and historian Dr. Alvarez Nazario speaking about the term Bomba tells us:

Etymologically, the term bomba goes back to a primitive Afronegroide form ngwoma ‘drum’, from which arose, in languages and dialects spread throughout the countries of Bantu Africa (Cameroon, Gabon, Congo, Angola, Mozambique, etc.), an infinite number of variants…”9

Although the word Bomba, as such, exists in the Kikongo language, we understand that Álvarez Nazario was right in making a connection between our Bomba drum and the Ngwoma.10 Further on Álvarez Nazario relates the Kokobalé to an ancient dance called Paracumbé and quotes a ‘Spanish-Portuguese couplet’ which reads (in translation):

Well what, don’t you know me?

The Paracumbé of Angola,…”11

The verse connects Kokobale with a root dance in Angola. There is enough evidence to substantiate the great Kongo-Angolan influence of Bomba, but for the purposes of this writing we will end this section with the following quote:

The introduction of blacks from Angola into Puerto Rico and other Spanish possessions of the “Indies”12 seems to date from the beginning of the trade in that region of Africa in the 16th century, the trade in black Angolans and Congos being particularly favoured by the various permits granted to the slave traders…”13

9 Álvarez Nazario, El Elemento Afronegroide en el Español de Puerto Rico, (San Juan, Puerto Rico: Instituto de Cultura de Puertorriqueña, 1974), 291.

10 Much more could be written on this subject, but we would like to keep this article brief.

11 Nazario, El Elemento Afronegroide, 311.

12 Name given to the American continent.

13 Nazario, El Elemento Afronegroide, 59.

2. In times of Marronage (and Slavery)

After the Haitian revolution (1791-1804), the fear of revolts and conspiracies grew among the Spanish settlers of the Boriken archipelago. In fact, the French government warned the Spanish government about the Haitians’ plans to help the enslaved people of the other islands to free themselves. Historian Luis M. Diaz Soler says in this regard:

…the French government informed the government in Madrid of having received news that Jean Jacques Desalines had sent emissaries to the European colonies in the Caribbean with the purpose of organising a general slave rebellion capable of putting an end to slavery in the Antillean area.”14

It is important to remember that drums, song, dance and ritual were central to the Haitian Revolution. This is the best example of what scholars call the Great Maroonage. A revolution of enslaved people who with sticks, machetes, and other arms fought for their freedom and for the freedom of their territory. To this day, stick and machete martial arts exist in Haiti, an example of which is the tire machèt.

For the next few decades the greatest fear of Europeans in the Caribbean was an Afro-descendant with machete in hand. From 1821 to 1826 there were several conspiracies, escapes and revolts of enslaved people in Borikén. This caused the governor at the time, Miguel de la Torre, to write a regulation, called the Rules of 1826, to regulate the life of the enslaved. Historian Guillermo Baralt states:

The main objective of the 1826 regulations was to prevent conspiracies and to frighten the slave with possible punishments and other measures that would be taken against him in case of uprising… To prevent the possibility of the use of the machete as a weapon during an uprising, it is stated in Chapter V, Article I, that in all the haciendas there should be a safe room, with a good key, to deposit the instruments of labour. This deposit would be the exclusive responsibility of the master or administrator and could not be entrusted to any slave.”15

This same phenomenon occurred in different parts of the Caribbean and Abya Yala. Fernandez Mendez speaking of the blacks of Martinique tells us:

At one time there were blacks in Martinique who by an intolerable abuse carried swords; but it has been ordered that they be taken away, because of the angry consequences that this could have, and they carry only a cane in their hand like lackeys.”16

14 Luis M. Diaz Soler, Historia de la esclavitud negra en Puerto Rico, (San Juan, Puerto Rico: La Editorial de la Universidad de Puerto Rico, 1953), 210.

15 Guillermo Baralt, Esclavos Rebeldes, (San Juan, Puerto Rico: Ediciones Huracán, 1982), 29.

16 E. Fernandez Méndez, Crónicas de las Poblaciones Negras del Caribe, (San Juan: Editorial Universidad de Puerto Rico, 1969), 119.

It is in this historical moment and in this context that we understand that the emphasis is placed on the Kokobalé as a stick dance or game, since the machete had been forbidden outside the work area, in the plantations or sugar cane fields, but the Bomba dance had been allowed17. Later we will see that according to the oral tradition preserved in the Cepeda family, the sticks are a substitute for the machete.

In my research this is consistent with what happens in other islands and countries in sister traditions such as, the tire machèt in Haiti, the mayolé in Guadeloupe, the sticklicking of Barbados, the calindá of Trinidad and New Orleans, the Esgrima de Machete of Colombia, etc. The anthropologist and archaeologist Tato Torres relating the Calindá of the Caribbean and New Orleans with the Kokobalé tells us:

This dance was also a ritualised fight or ‘game’, accompanied by drums. Calindá was a combat or warrior dance similar to Brazilian capoeira and to the dance identified in Puerto Rico as cocobalé, performed with sticks and simulating combat between opposing groups. ”18.

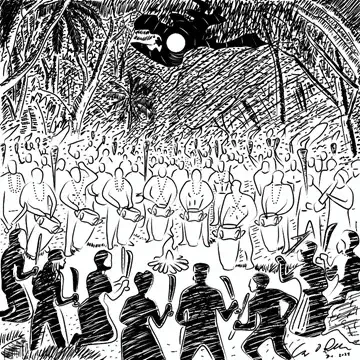

The music and martial traditions are part of this heritage that served as a basis for the defence and struggles in the different manifestations of the marronage. In Borikén, Bomba played a major role in the struggles for freedom. Baralt states in his book Esclavos Rebeldes that ‘dancing and drumming created a sense of cohesion among the slave population. However, the dance was only a disguise to cover up the slaves ‘subversive aims’.19

War dances date back to time immemorial in Africa. Following this ancestral knowledge, the techniques of the arts of warfare, with and without weapons, were codified into dance movements in Bomba dances, as happened elsewhere in the Caribbean and Abya Yala, as in the case of Capoeira. Dr. Noel Allende Goitía seems to agree with this position when he defines Kokobalé as follows:

Cocobalé is an Afro-Boricua dance practice developed by enslaved warriors. One could speculate that it was in response to the regulations codified in the “Bandos contra la raza negra” and the “Bandos de policía y buen gobierno”, which punished blacks and mulattos with harsh penalties for carrying weapons. Cocobale is a relative of stick fight dances, practised throughout the English, French, Dutch and Danish West Indies, and capoeira, in Brazil.” 20.

Years after the prohibition of the machete outside the cane fields, Juan Prim became governor. Following the same regulatory idea to avoid riots, he drafted the Edict Against the Black Race (Bando Contra la Raza Negra). Given the common use of sticks as weapons, Article III of this regulation even criminalised threatening with a stick:

… if a Negro insulted by word, or mistreated or threatened with a stick … he would be sentenced to five years imprisonment … The master was empowered (Article V) to kill the slave who revolted in a similar act.”21.

The researcher José Fernández, reflecting on Kokobalé and marronage, states that:

In the times of slavery and during the Marronage it was used to develop bravery, character, fortitude and skill to face the enemy. In Puerto Rico it survived as a bomba dance.”22.

17 I believe that people in the past emphasized more the dance aspect of Kokobalé.

18 Torres,”Cocobalé”,12-16.

19 Baralt, Esclavos Rebeldes, 66.

20 Allende Goitía, “Las músicas de las identidades post-puertorriqueñas”, 80 Grados, 2022, https://www.80grados.net/las-musicas-de-las-identidades-post-puertorriquenas/.

21 Baralt, Esclavos Rebeldes, 130.

22 Fernández, De Bomba y de Bombeadores, 67.

References

Baralt, Guillermo. Esclavos Rebeldes. San Juan, Puerto Rico: Ediciones Huracán, 1982.

Brooks, Jerome. “Chinua Achebe. The Art of Fiction, no 139”. The Paris Review (133), Winter 1994. https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/1720/the-art-of-fiction-no-139-chinua-achebe.

Diaz Soler, Luis M. Historia de la esclavitud negra en Puerto Rico. San Juan, Puerto Rico: La Editorial de la Universidad de Puerto Rico, 1953.

Goitía, Noel Allende. “Las músicas de las identidades post-puertorriqueñas.” 80 Grados Revista Digital, 2022.

https://www.80grados.net/las-musicas-de-las-identidades-post-puertorriquenas/

Méndez, E. Fernández. Crónicas de las Poblaciones Negras del Caribe. San Juan: Editorial Universidad de Puerto Rico, 1969.

Morales, José Fernández. De Bomba y de Bombeadores. San Juan, Puerto Rico: BiblioGraficas, 2021.

Nazario, Álvarez. El Elemento Afronegroide en el Español de Puerto Rico. San Juan, Puerto Rico: Instituto de Cultura de Puertorriqueña, 1974.

Ortiz, P. Lebrón. Filosofía del Cimarronaje. Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico: Editora Educación Emergente, 2020.

“The origins of capoeira?”, CapoeiraHistory, October 17, 2020. https://capoeirahistory.com/pt-br/as-origens-da-capoeira/.

Thompson, Alvin O. Huida a la libertad. Fugitivos y cimarrones africanos en el Caribe. México, D.F., Siglo XXI Editores, 2005.

Torres, Carlos Tato . “Cocobalé”: artes marciales africanas en la bomba”. Revista Güiro y Maraca, Vol. 5, no. 1, 2001.