Martial arts and music. A comparison of muay thai, pencak silat, capoeira and taekkyeon.

.

By Néstor Vega González.

In this article we will compare four martial system’s use of music and dance-like movements: muay thai, pencak silat, capoeira and taekkyeon. We will briefly describe how each one’s movements relate to the music present during their performance, as well as highlight their points of convergence and those of disparity.

In his cross-study of capoeira and muay thai, Duncan Williams first notes that the main common characteristic of its music is “their commitment to physicality” (2015, 2). His research shows that, in muay thai, “the tempo of the music is increased and more syncopated rhythms are chosen as the musicians improvise in direct response to the fight itself, reflecting the actions of the fighters” (Moore, 1969; citado em Williams, 2015, 4). It is important to note that, as the fight progresses –especially in the later rounds– the tempo increases to nearly the double of the first movements. With regard to musical comparison, Williams concluded:

In capoeira, the berimbau may provide rhythm and syncopation, or set the pulse, depending on the toque, whilst the accompanying percussion sets the pulse (in the traditional capoeira angola, the bateria will be completed by pandeiros, atabaque, reco-reco and the agogô bell). In Thai sarama [muay thai‘s orchestra], the low tuned percussion provides rhythm and syncopation but is never used to set the pulse –contrary to the use of, for example, kick drums in Western popular music. Instead, the pulse is set by the small percussion, usually the ching cymbals, which share some acoustic range and purpose with the high percussion in the bateria” (2015, 13).

During the early rounds of a muay thai match, if sarama is played live with musicians, they will follow the rhythm of the fighters. Since in them, the fighters are often measuring each others, their tempo is more unpredictable compared to the later rounds, when they are likely to be beaten and fatigued. It is then that the musicians will take a more active role, haranguing the fighters into action. Thus, it is considered that sarama “helps create more drama, and fans get into the fights more as the intensity grows. [It] has a way of psychologically manipulating the crowd and even the fighters” (Bradshaw, 2023 [sem paginação]). Just as Thailand’s culture and its national sport has modernized, so has sarama, merging it with hip-hop beats and techno music (ibid.). However, its fundamental role remains the same; that is, to reinforce the rhythm of the fight and its emotional impact, thus deepening the experience of combat.

While muay thai has been greatly demystified and westernized with its global spread as a combat sport (cf. Vail, 2014, p. 532), pencak silat has remained mostly localised in its countries of origin, focused on its traditions and with a performative rather than combative aim.

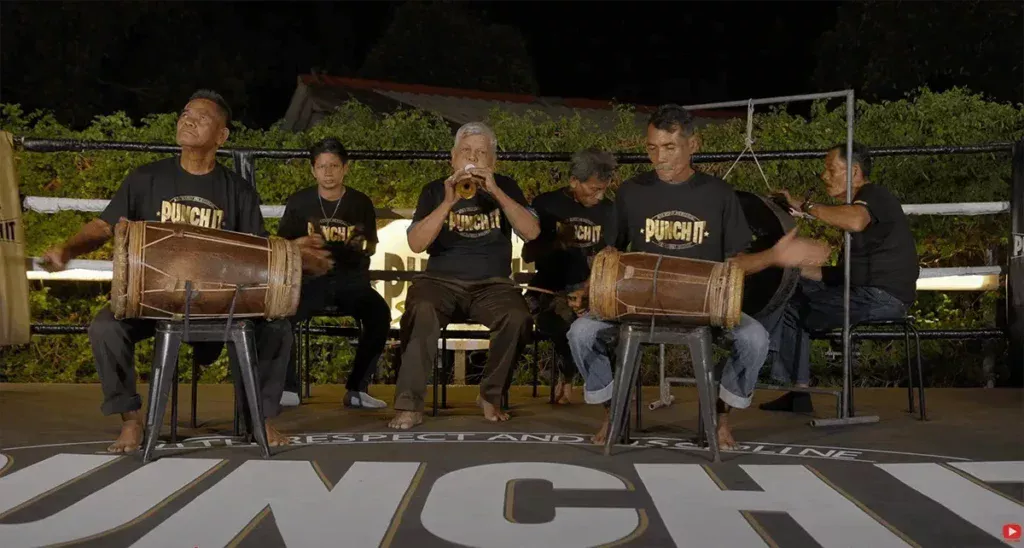

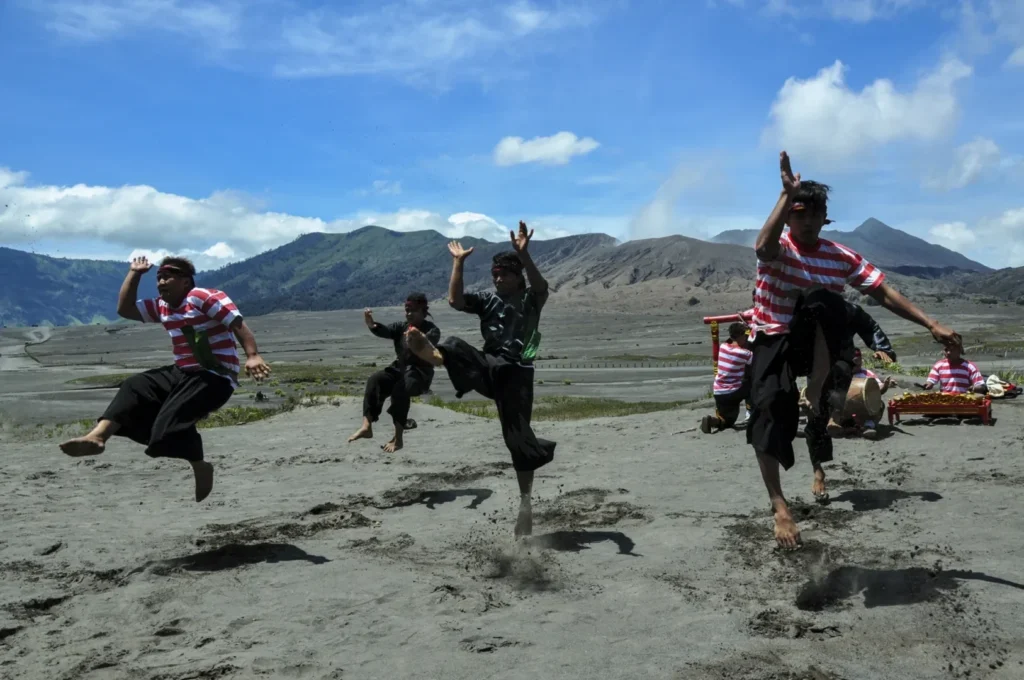

There are many styles and schools of silat in Indonesia, the Philippines and Malaysia. To the effect of this study, we will approach the system in a generalist way. Silat’s musicians have distinct ways to announce the movement of the performer, using diverse percussive accents. Their style is so specific that “the idiosyncrasies of musical annunciation can be particular to each pencak silat performer. Through differences in musical annunciation, an experience listener can identify who may be performing, even without seeing him” (Paetzold, 2016, p. 81)

Silat’s musical instruments are closely related to the muay thai arrangements. In both systems we can find a prevalence of percussion with instruments like kendang drums in silat or the klong khaek drums in muay thai; as well as metal-percussion like gongs, the saron or the kendong in silat and the cymbal-like ching in muay thai. They are accompanied by oboe-like wind instruments: the serunai in silat and the pi chawaa in muay thai.

Silat’s orchestra or gamelan also employs a bamboo flute called suling. Sarama is comparatively more homogeneous than silat music, where variations in its instruments’ size and length shape the different melodic and performative styles of silat. The key difference is that while in muay thai the musicians influence the practitioners’ action; in silat, musicians play according to their performance. As Paul H. Mason states:

The musicians attempt to animate the punches and kicks of the performances with appropriately placed slaps of the drums […] The drums follow the movements of the performer with their playing, and develop great sensitivity to the choreographed movements of the art form. […] The music is loud, and the audiences love to add to the atmosphere by shouting in time with the music and crying out their support for the performers (2016, 244-245).

Both muay thai and pencak silat deal with an issue that affects their contemporary practice: the abandonment of live musical performances in favour of pre-recorded themes, tunes and songs. This is, of course, a matter of budgetary and logistic convenience. This matter has had various repercussions on both disciplines, mainly –and especially among purists– a loss of its traditional and ancient character unmediated by modern technology. In muay thai, we have personally observed that, in the absence of musicians playing live, it is often the organizers, referees and annunciators are the ones calling out the fighter’s lack of aggression. In silat, experts find that performances “have become fixed, and completely reliant on the standardised movement patterns” (Paetzold, 2016, 100). As researchers Allen Fogelsanger and Kathleya Afanador put it:

Music requires the movement of musicians, but the invention of sound recording broke that intimate connection. Recorded sound limits the interaction of music and dance, for while dancers may still respond to music, without musicians the music cannot respond to dance” (2006; em Mason, 2016, p. 256).

In other words, the researchers sought to highlight the physicality of the musicians’ own movement as they played their instruments, that underlying performativity that operates in concert with that of the fighters. The convenience of pre-recorded music entails the loss of bidirectionality in the reactive dialogue between them, as well as their vital connection.

Taekkyeon

Moving on to other systems, we find that taekkyeon is diametrically opposed to capoeira in its relationship to music. Although both contain dance-like rhythms and movements, they seem to be antithetical in every other way. In terms of movement and technique, the Korean system favours upright stances while capoeira makes use of crouching postures whose angles of attack are based on changes in level.

Taekkyeon is usually performed in a traditional way, demonstrating a set choreography of movements in which there can be found a rhythmic rocking of the body, similar to that of ginga, although not as dynamic and more contained in its development in space.

There are three major schools of taekkyeon: the Korean Taekkyon Association, which promoted its inscription into the Intangible Cultural Heritage list(UNESCO, 2011); the Korea Taekkyon Federation (KTF), affiliated to the Korea Sports & Olympic Committee (KSOC), membr of the International Olympic Committee (s. Kwon, 2024 [no pagination]); and the Kyunlyun school, which is especially popular in Seoul. The more traditional approach of the Korea Taekkyon Association doesn’t seem to incorporate music in its regular practice. Both the KTF and the Kyunlyun schools have a combative modality in which the goal is to kick the opponent in the head or take them down with a sweep or throw. While the KTF holds large scale events with weight clases, the Kyunlyun’s events seem to be more informal. These are battle-type matches, held every summer in Seoul’s Insandong district.

In its performative and combative forms, music doesn’t usually seem to be played along the action itself. Rather, it is played in between matches or demonstrations. We have found, however, that there can be exceptions to this on extraordinary occasions. In the 2024 Championships organised by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism Cup National Taekkyon, the KFT held competitive-exhibition team matches in which choreographies were performed accompanied by contemporary music and even combining taekkyeon with conventional dance moves. This would be analogous to muay thai’s incorporation of hip-hop beats. During the 31st Martial Arts Festival in Paris-Bercy (2016) traditional Korean instruments were played along the demonstration performed by Master Mun and Jean-Sébastien Bressy’s team. Said instruments were drums such as the buk and the changgu; and gongs like the bigger ching and the smaller, hand-held kkwaenggwari.

Kim Duk-soo leading performers of samulnori, traditional Korean percussion music, during the opening ceremony for the Culture City of East Asia in 2015. Two kkwaenggwari hand-held gongs on the left and the right, a ching at the background, a changgu drum at the centre and a buk drum on the right can be seen. © Ministério da Cultura, Esportes e Turismo (Coreia do Sul) CC BY-SA 4.0

Therefore, taekkyeon rarely presents live music simultaneously to its action. In the few cases it does, its instruments seem to be less varied compared to capoeira’s. Unlike capoeira, taekkyeon does not seem to involve vocals or clapping, which are unmediated channels for practitioners and spectators to directly participate through music.

As a closure to this text, we should like point to the value of comparative and interdisciplinary studies such as ours. While they may not reach the depth each singular system deserves by itself, these methods may delineate connections and points of view that may not seem too obvious at a first glance. Moreover, they can in our opinion enrich and extend the interrelationship between martial cultures and communities, furthering their knowledge and experience.

Néstor Vega González graduated in Fine Arts under the University of Salamanca (USAL) and is currently studying his PhD under the Fine Arts Doctorate Program of the Complutense University of Madrid (UCM). He is a researcher in training in the UCM’s Drawing and Engraving Department, and a member of the Research Group Psicosociobiología de la violencia: Educación y prevención, of UCM’s Education Faculty.

References

Bradshaw, B. “Muay Thai Music – Sarama,” MuayThai.com, accessed February 13, 2025, https://muaythai.com/muay-thai-music-sarama/.

Karaté Bushido Officiel Le Taekkyon au 31e Festival des Arts Martiaux! 2016. [Video], accessed February 13, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8sZ9BLpT6b0.

Kwon, S. M. “How long will it take for Taekkyon to go from the National to the Olympics?”, WMNews, accessed February 13, 2025, http://www.wmnews.kr/571.

Mason, P. H. “Pencak Silat Seni in West Java, Indonesia.” In The Fighting Art of Pencak Silat and Its Music: From Southeast Asian Village to Global Movement, edited by Paetzold, U. U. and Mason, P. H. Leiden: Brill, p. 235-262.

Paetzold, U. U. “The Music in Pencak Silat Arts Tournaments is Gone – A Critical Discussion of the Changes in a Performance Culture.” In The Fighting Art of Pencak Silat and Its Music: From Southeast Asian Village to Global Movement, edited by Paetzold, U. U. and Mason, P. H.. Leiden: Brill, p. 76-122.

Taekkyeon, a traditional Korean Martial Art , 2011 [Video]. Produced by United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), accessed February 13, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ga1Im-3ZtH8.

Vail, P. “Muay Thai: Inventing Tradition for a National Symbol”, Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia, 29, nº3 (2014), p. 509-553. DOI:10.1355/sj29-3a.

Williams, D. “A Short Cross-Analysis of Brazilian Capoeira and Thai Sarama Music and Shared Ritual Practices”, Analytical Approaches to World Music, 4, nº1, (2015), accessed February 13, 2025, https://iftawm.org/journal/oldsite/articles/2015a/Williams_AAWM_Vol_4_1.html.

대한택견회 [Korea Taekkyon Federation (TKF)] (2021) 제17회 대통령기 전국택견대회 2일차_태권도원 평원관 [Day 2 of the 17th Presidential National Championship – Taekwondowon Pyeongwon Hall] [Video]. accessed February 13, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=ohj2cviguMk&list=WL&index=3&t=15316s.