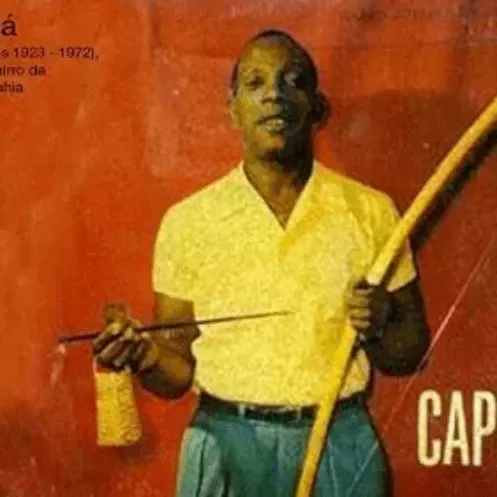

Anníbal Burlamaqui, customs officer and poet; Master Zuma, capoeira and boxeur (1898-1965)

By Ana Paula Höfling

On August 18, 1965, the Jornal do Brasil published a note where Mrs. Burlamaqui and family expressed their gratitude for the condolences received; Anníbal Z. M. Burlamaqui, the author of the influential 1928 capoeira manual Gymnástica Nacional (capoeiragem) methodisada e regrada, was dead at the age of sixty-seven.1 Burlamaqui, whose booklet galvanized efforts to move capoeiragem from the police pages to the sports pages of Rio’s newspapers—to legitimize and de-stigmatize this Afro-Brazilian combat game— was among a growing number of enthusiasts of gymnástica nacional (national gymnastics), a strategic re-naming of a practice that was prohibited by law as capoeiragem.2

It is unclear with whom Burlamaqui studied capoeiragem and for how long; what is clear is that in Rio de Janeiro in the 1920s there was no shortage of opportunities to study national gymnastics. Burlamaqui could have studied in formal learning spaces such as the Gymnástico Português, where physical education teacher Mario Aleixo taught national gymnastics since 1920, or he may have joined men practicing “capoeiragem exercises” in public spaces such as Rio de Janeiro’s plazas and squares.3 Under the nickname Zuma, he competed in matches throughout the late 1910s and early 1920s using both his boxing and capoeiragem skills.4

Although we don’t know very much about Zuma—the sportsman, capoeira, and boxeur–beyond his influential 1928 publication, we do know bits and pieces about Burlamaqui’s life beyond capoeiragem: he worked as a customs enforcement officer (guarda da polícia aduaneira)5 and was a member of the Niterói-based literary society Cenáculo Fluminense de História e Letras (Rio de Janeiro’s State Society of History and Letters), which he joined on March 8, 1930, occupying chair number 33.6 In the 1950s, as part of the directorial board, he was a member of the committee on writing and peer review (redação e parecer) and he was elected president of the society twice.

The Cenáculo hosted poetry readings and music recitals, and sponsored publications of books written by its members, such as Burlamaqui’s book of erotic poetry, O meu delírio: poêma do instinto (My delirium: a poem of instinct) published in 1939, a book that reveals Burlamaqui as a passionate man who dared express his lust and desire in writing.7 Burlamaqui’s life was led by curiosity; his willingness to see beyond the accepted norms of his time made him “a man ahead of his time” while being very much of his time—a carioca intellectual and sportsman steeped in Brazilian modernity.

As Zuma, the sportsman, and as Burlamaqui, the writer, Anníbal seemed like the perfect person to publish a book that would support the ongoing efforts of de-stigmatization of capoeiragem spearheaded by several other white, middle-class, well-educated carioca capoeira enthusiasts, such as journalist and cartoonist Raul Pederneiras.

In a two-column article published in the Jornal do Brasil in the same year Zuma’s book was published, Pederneiras, signing as just Raul, mentions previous failed efforts of organizing and creating a method for “Brazilian gymnastics,” and praises Gymnástica Nacional as a much-awaited methodization of this practice: “a work of great utility which should contribute to the adoption of this national sport in gymnasia with great probability of success. The sure proof of this success is the great demand for Zuma’s book, which makes a great contribution that allows us cultivate and appreciate, with efficacious results, that which is ours, which is very Brazilian.”8

It is clear that the Zuma’s main goal in Gymnástica Nacional was to legitimize the practice—to remove the stigma from capoeiragem.9 Dr. Mario Santos, who wrote the book’s preface and who also posed as Zuma’s opponent in the twenty photographs that illustrate the book, cites the legitimization of English boxing, French savate and Japanese jiu-jitsu as precedent and asks: “Why […] would capoeiragem, in Brazil, escape the evolutionary march or its sister forms? […] Why should we not create rules and regenerate capoeiragem?”10

Throughout the book, Zuma does just that. Drawing from two popular imported sports, boxing and “foot-ball” (soccer), Zuma prescribes the diameter of the circular playing field, the starting position of the contenders, the duration for each round (three minutes, with a rest of two minutes), and the criteria for establishing a winner for each match: a fighter would win either by incapacitating the opponent, or, if so agreed beforehand, points would be counted by a referee who would proclaim the fighter who caused the most falls as the winner.11 With these rules, Zuma hopes to mainstream capoeiragem, turning it into a form of “self-defense, a sport like any other.”12

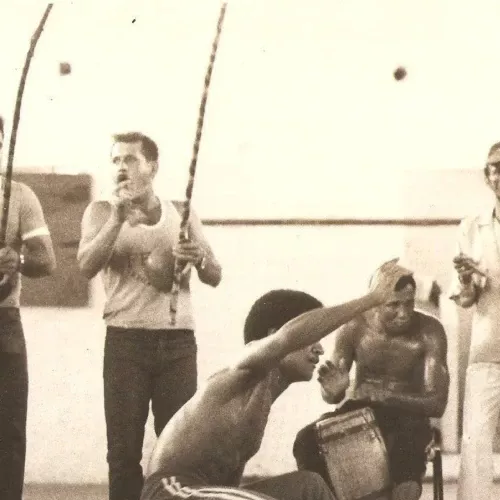

While many of Zuma’s rules—the presence of a referee, a point system, a match divided into timed rounds—clearly constitute borrowings from foreign sports, Zuma rearticulates street capoeiragem in hegemonic terms through these foreign borrowings. While much attention has been paid to Zuma’s rules for capoeira matches—his methodization—and the evolutionist language of “improvement” that permeates the text, the photographs provide ample evidence that Zuma’s practice was grounded in street capoeiragem. Both the rich movement descriptions and the photographs that illustrate Gymnástica Nacional attest to Zuma’s in-depth knowledge of the practice; it is likely that he had been training for at least a decade by the time he published the book.

Zuma instructs the reader on the proper stance for the guarda: “one brings the body upright, in a natural alignment, in a noble and erect attitude, twisting to the right or the left.”13 However, in more than half of the photos in the book the players appear crouched low and bearing weight on the hands, contradicting this upright, “noble” and erect stance.

Zuma and Santos demonstrate a technique that demanded movement close to the ground, either by ducking under a kick or initiating a kick from below. The erect stance of the guarda, which Zuma further describes as “the first position, noble and loyal,” remains almost entirely rhetorical, invoking nobility as part of his effort to remove the stigma that marred the practice of capoeira in the early twentieth century.14

The bulk of Zuma’s attacks and defenses are based on leg sweeps and kicks rather than punches or strikes with the hands, precisely because the hands are instead used for supporting the weight of the body. Freeing the feet to attack by placing the palms of hands on the floor, Zuma’s capoeiragem demands that players constantly shift weight from feet to hands and from hands to feet. Zuma’s technique has been interpreted as a stiff, upright version of capoeiragem where movements do not flow from one another. However, a reader following Zuma’s descriptions and instructions would constantly rise, fall, dive, duck and jump.

The text provides ample evidence of sustained interaction, and in fact Zuma instructs his readers to initiate an attack from a defensive move, in the same way that strikes and evasive maneuvers flow from each other in present-day capoeira. A move Zuma calls pentear (to comb) or peneirar (to sift) not only gives further evidence of the game’s flow, but also embodies tapeação (trickery), the element of deception central to capoeira and capoeiragem. Zuma instructs: “One throws the arms and the body in every direction in a ginga, in order to disturb the attention of the adversary and better prepare for the decisive attack.”15

Contrary to today’s understanding of the ginga in capoeira practice as a basic connecting step, Zuma’s peneirar has the express intention to confuse and deceive, a tactical maneuver in preparation for an attack. Deception, trickery and unpredictability, the same tactics consider foundational to capoeira today, run through Zuma’s Gymnástica Nacional.

Descriptions of capoeiragem that precede the publication of Gymnástica Nacional point to several continuities between Zuma’s national gymnastics and nineteenth-century street capoeiragem. In one of the earliest detailed movement descriptions of capoeiragem, included in Brazilian folklorist Alexandre Mello Moraes Filho’s 1893 Festas e tradições populares do Brasil, we find accounts of several moves almost identical to the ones included in Zuma’s Gymnástica Nacional. More than half of the strikes mentioned by Mello Moraes are also found in Zuma’s book: the rabo de arraia, cabeçada, rasteira, escorão (straight kick to the adversary’s stomach), and tombo da ladeira (tripping a jumping adversary).16

Likewise, descriptions by Plácido de Abreu (1886), Raul Pederneiras (1921;1926) and Henrique Coelho Netto (1928) attest to a capoeiragem not dissimilar to Zuma’s national gymnastics. Zuma did take credit for inventing three new moves listed in the book: the queixada (kick to the chin), the passo da cegonha (lit. stork’s step, where the defending player grabs the attacker’s raised leg while sweeping his standing leg) and the espada (lit. sword, a kick aimed at disarming the opponent).17 While Zuma undoubtedly sought to “improve” capoeiragem through codification, he also championed its intrinsic value: capoeiragem “encompasses, albeit still a little confused and ill-defined, all the elements for a perfect physical culture.”18

In fact, he proposed capoeiragem as a tool of self-improvement for young “family” men; cultivating the body through capoeiragem, Brazilian men would become “strong, feared, brave and daring.”19 If all young men learned capoeiragem, Zuma predicted, the Brazilian citizen of the future would be “respected, feared [and] strong.”20 Although he proposes to “improve” capoeiragem, Zuma imagines a Brazilian “citizen of the future” improved through an Afro-diasporic practice that already encompassed all the elements for a perfect physical culture. Cultivating both body and body politic through an Afro-diasporic game turned eugenicist thought on its head, allowing Africanity to be viewed as a source of “regeneration” rather than degeneration, and as a source of strength and national pride.

1 André Luis Lacé Lopes reports Burlamaqui’s birthdate as November 25th, 1898. A capoeiragem no Rio de Janeiro: primeiro ensaio, Sinhozinho e Rudolf Hermanny. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Europa, 2002, 88.

2 In the mid 1910s, a few reports of matches of capoeiragem began appearing in the sports pages of the Jornal do Brasil, although at this time news of capoeiragem still appeared primarily in the “complaints” column of this newspaper and in its police pages, where it was associated with stabbings and murders.

3 Newspapers report regular daily practice of capoeiragem in public spaces in the 1910s and 20s in Rio de Janeiro, often in a public complaints column (such as the “Queixas do povo” column in the Jornal do Brasil). “Exercises of capoeiragem” took place at various plazas in the city, such as Praça Quinze de Novembro and Praça Onze de Junho, as well as train stations, residential street corners, and various locations in the suburbs (Engenho de Dentro, Cascadura, and Rocha).

4 In a note in the sports page of the Correio da Manhã on April 20th, 1920, and in a note in O Jornal on April 19th, 1920, Zuma is referred to as “capoeira and boxeur.” In the book, Zuma explains that his nickname was derived from his second name; his full name was Anníbal Zumalacaraguhy de Menck Burlamaqui. Anníbal Burlamaqui, Gymnastica Nacional (capoeiragem) methodizada e regrada (Rio de Janeiro: n.p., 1928), 15; Ulysses Burlamaqui, personal communication.

5 He is referred to as a “guarda da polícia aduaneira” in a newspaper article recounting a tricky situation where the male officers had to find a creative solution to be able to search a woman suspected of carrying contraband under her skirt. “Um contrabando complicado e engraçado,” Correio da Manhã, June 15th, 1924; He rose through the ranks and reached the position of tax auditor at the Brazilian revenue service (Receita Federal). Ulysses Burlamaqui, personal communication.

6 “Posse do novo acadêmico,” Jornal do Brasil, March 2, 1930.

7 The book received a mixed review in the Jornal do Brasil, and a scathing review in the Correio da Manhã. “Registro Literário,” Jornal do Brasil, April 14, 1939; Álvaro Lins, “Critica Literária—Poesia,” Correio da Manhã, November 16, 1940. He also published a second book of poetry, titled Babel de Emoções. Ulysses Burlamaqui, personal communication.

8 Raul Pederneiras, “A Gymnastica Nacional,” Jornal do Brasil, April 22, 1928.

9 For a close reading of Zuma’s Gymnástica nacional, see Ana Paula Höfling, Staging Brazil: choreographies of capoeira. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2019.

10 Burlamaqui, Gymnastica nacional, 4.

11 Burlamaqui, Gymnastica nacional, 18-19.

12 Ibid., 15.

13 Ibid., 23.

14 Ibid.

15 Burlamaqui, Gymnastica nacional, 42.

16 Alexandre José de Mello Moraes Filho, Festas e tradições populares do Brasil. (Rio de Janeiro: F. Briguiet, 1946 [1893]), 448.

17 Ibid., 21.

18 Ibid, 13.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid., 15.

Works cited:

Rio de Janeiro newspapers consulted at the newspaper database (hemeroteca) of the Biblioteca Nacional:

- Jornal do Brasil

- Correio da Manhã

- O Jornal

Abreu, Plácido de. Os capoeiras. Rio de Janeiro: Typ. da Escola de Serafim José Alves, 1886.

Burlamaqui, Anníbal. Gymnastica nacional (capoeiragem) methodisada e regrada. Rio de Janeiro: n.p., 1928.

__________. O meu delírio: poêma do instinto. N.p.: Cenáculo Fluminense de História e Letras, 1939.

Burlamaqui, Ulysses Petronio. Personal communication. June 19, 2020.

Coelho Netto, Henrique. “Nosso jogo.” In Bazar. Rio de Janeiro: Livraria Chardron, de Lello e Irmão, Ltda Editores, 1928.

Höfling, Ana Paula. Staging Brazil: choreographies of capoeira. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2019.

Lopes, André Luiz Lacé. A capoeiragem no Rio de Janeiro: primeiro ensaio, Sinhozinho e Rudolf Hermanny. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Europa, 2002.

Mello Moraes Filho, Alexandre José de. Festas e tradições populares do Brasil. Third edition. Rio de Janeiro: F. Briguiet, 1946 [1893].

Silva, Elton and Eduardo Corrêa. Muito antes do MMA: O legado dos precursores do Vale Tudo no Brasil e no mundo. Kindle edition, 2020.

For a close reading of Zuma’s Gymnástica nacional, see Ana Paula Höfling, Staging Brazil: choreographies of capoeira. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2019.

Ana Paula Höfling, University of North Carolina, Greensboro