By Letícia Vidor de Sousa Reis.

Introduction

We live in a country where violence against women is naturalised. Blaming women for the violence of others is a patriarchal strategy that happens in many cases and covers up the aggressor’s identity and crime. Women need to be heard and listened to by men as well as women from older generations so that together, our sisters, daughters and nieces do not have to go through what so many other women endured. Directly related to this topic comes the issue of sexual assault in the Brazilian capoeira community, within and outside rodas.

The capoeira scene has undergone a transformation over the last forty years, not only due to a rise in numbers with more women joining, but also due to the fact that they realise they are living in a hostile and dangerous space.” (Note from Grupo Nzinga de Capoeira for the end of gender violence, 2020).

Capoeira women in the past

Criminal proceedings against female capoeiras are quite rare. Pires, in his work A capoeira na Bahia de Todos os Santos (2004), sought to trace the social history of capoeira between 1890 and 1930. The small number of women (3%) among those prosecuted for homicide and bodily injuries demonstrated that during this period, capoeira practitioners in Salvador were predominantly men.

One of those proceedings refers to a Bahian washerwoman, Maria Elisa do Espírito Santo, who, in 1910, was at her workplace when an incident occurred.

She claimed to have forgotten her mistress’s towel at the fountain of Baixa das Quintas, where she washed her clothes, to earn her and her family’s livelihood. She went back to the fountain and started looking for the towel among the belongings of two co-workers, because, in the end, it could only be with another washerwoman’s things.” (Pires: 2004: 113-114).

The washerwomen who were there denied her accusations, and Maria Elisa, dismayed, uttered “obscene words” to “an elderly black lady”. Manoel de Santana, who had a hardware store nearby, overheard the ongoing conversation and got involved in a physical confrontation with Maria Elisa, injuring her arm with a machete.

The previously mentioned black woman, seeing her wounded, hurried to return the towel. Thus, Maria Elisa wrapped the towel around her good arm (…) “Here is the proof: the towel stained with blood.” (Pires: 2004: 114).

Probably because she was unable to pay her mistress for the loss of the towel and was quite nervous, Maria Elisa started a fight with Manoel Santana. “[In this situation], seeing herself cornered and at a disadvantage, she used the only weapon available to her in that moment and attacked her opponent with capoeira moves” (Pires, 113-114).

In his work Culturas Circulares (2010), Pires, based on the assumption that capoeira is part of urban working-class culture, carried out a study on the Cariocan (from Rio de Janeiro) capoeira groups in the last decades of the nineteenth century, until about the 1920s, based on police documents. Women have been involved in capoeira since the First Republic, even if in very small numbers, and their existence was very rarely documented, adding up to only 7.1% among those recorded for practicing capoeira, which is predominantly male.

Although, capoeiristas were generally considered vagrants, this clashed with the collected evidence. Ana Maria da Conceição, for example, was arrested in 1906 for doing “body agility exercises” but presented a certificate that she worked as a cook. So, despite practicing capoeira, she was acquitted (Pires: 2010: 114). Another case which also took place in 1906 involves a family. The police officer who participated in the arrest claimed that the group was “playing capoeira” and said

That the two male defendants [were] causing disturbances and that the three female defendants also present [were] upsetting the neighbourhood and [startling them] with threats and antics [and] jumping around with their arms and legs.” (Pires: 2010: 113)

New paths for capoeiristas

The number of women interested in capoeira has grown since the 1970s. As Lima (2016) pointed out, ethnomusicologist Emília Biancardi is one of the main responsibles for the promotion of capoeira in Brazil and abroad. In 1962, she created the group Viva Bahia in a public school in Salvador (BA) and from then onwards the capoeira established itself as an artistic spectacle for its own promotion . Moreover, this made it possible for capoeiristas to perform abroad.

Christine Zonzon (2017) proposed to tackle one of the themes that she maintains is a taboo in capoeira studies – women’s bodies. Her main research focus was the invisibility of women in the Capoeira Angola roda. According to the author, it is in the street rodas where the small presence of capoeirista women is most noticeable:

The absence of female capoeiristas in traditional capoeira spaces / practices becomes even more evident in street rodas, as it is precisely in this “open” ceremony that the number of women and their bodies, their actions and the spaces they occupy in the roda are even more diminished.” (idem, p. 302).

The obstacles for female capoeiristas are not restricted to playing the berimbau or being the lead singer. According the author, “it also includes values of excellence, such as rising in the group’s hierarchy”. However, this does not prevent them from dedicating themselves to capoeira. A young Angolan woman explains that: “Capoeira helps me to work out certain ways of being in the world that I wouldn’t have otherwise. It is work in action; it is in the body ” (2017: 304).

Many female capoeiristas emphasize the lack of recognition and the devaluation they experience. However, the author believes that:

The inclusion of gender equality in the agendas of groups (which is also associated with the anti-racist struggle, notably via the “black woman”) testifies to this phenomenon, since it questions the assignment of knowledge and powers enforced in traditional society.” (2017: 306).

In other words, some female capoeiristas believe that rodas exclusive to women can help fight gender discrimination in capoeira.

The representation of women in capoeira songs

As with other Afro-Brazilian art forms, oral communication is the basis of the transmission of knowledge and tradition. In capoeira, songs are one of the most important records of collective memory. In these songs, several representations of the woman can be observed. One of them is that of an unfaithful woman or “traitor”. One song says: She has a gold tooth / It was I who ordered it to be placed / I am going to plague her with a plague / For this tooth to break / She does not remember me / I will not remember her either. (public domain)

Another representation is that of the jealous woman, who, for this particular reason, makes it difficult for her partner to maintain relationships with other women, as can be seen in this song: The straw house is a hut / If I were fire I would burn it / Every woman is jealous / If I were the Death I would kill her, mate. (public domain)

The woman also plays the role of a mother who is sometimes careless, since she is supposedly the sole carer for the child: Cry boy! / Nhem, nhem, nhem / The boy cried / Nhem, nhem, nhem / If the boy cries / Nhem, nhem, nhem / It’s because he didn’t suckle / Nhem, nhem, nhem / Shut up boy! / Nhem, nhem, nhem (public domain).

Another image of women in capoeira songs seems them as the beatified mother of God, as demonstrated in this farewell song, sung at the end of the capoeira roda: Goodbye, goodbye / Farewell! / I’m leaving / Farewell! / I’m going with God / Farewell! / And Our Lady Farewell! (public domain).

Women’s sexual harassment is one of the key current problems which was discussed at a meeting in Campos (RJ) in 2019. For Argentine journalist and capoeirista Silvina, women need to be heard:

As a social communicator, female capoeirista, a defender of human, animal, and environmental rights, I want you to understand the importance of stopping to think and reflect on the difficulties that we, women, suffer both in sport and daily life.”

According to Mannu, the coordinator of the United Black Youth Movement (MNURJ, Juventude do Movimento Negro Unificado): “In the 21st century, with the admission of women in sports such as capoeira, machismo and sexism are still present (…) [Through debates, it is possible] to disentangle the issue of harassment”. According to social scientist and capoeirista Jhe, it is essential that men and boys take part in this discussion so that they do not continue and reproduce this model of machismo. [Some people think] “that harassment is just sexual abuse, but some of the subtler aspects of harassment are often not considered” (Capoeira women discuss harassment in Campos, 2019).

Initiatives to empower women in capoeira

Mestra Cigana Capoeira

At that time, the prejudice against female capoeiristas was quite obvious. Cigana married a successful engineer because she couldn’t bear to live with her family anymore, who rejected her for being a capoeirista. Her husband also demanded that she choose between capoeira or living with him and their three children, all still quite young. She laments: “I will never forget the custody hearing of my 1-year-old son; my ex-husband exclaiming: “- Excellency, she is a capoeirista! And the judge replied: ´- But you are going to quit capoeira, aren’t you? “

And she explains to the journalist: “(…) Capoeira was my ideal, my philosophy of life and I chose it”. She was the only woman to participate in her master’s rodas, and remembers the difficulty in interacting with other capoeiristas, since as a woman, “she was invisible”. She complains: “(…) I would spend hours at the foot of the berimbau, asking for permission to enter, and when I finally managed to get in I couldn’t even stay 30 seconds before they took me out [of the roda]”.

In 1975 she met Mestre Canjiquinha in São Paulo and went with him to Salvador (BA). After five years of training, she became the first female capoeira master in Brazil. Mestra Cigana did not stay in any group for long. She revealed that one of the main reasons was that she refused to yield to the masters’ sexual harassment.

A documentary about Mestra Cigana Capoeira is being prepared at the moment – it is still in the material gathering stage. Photos, magazines, documents and more will be collected. The main objective is to reconstruct her route in the cities of Salvador, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Volta Redonda.

Upon returning to her hometown, Cigana opened the Associação Mestre Canjiquinha, where she had more than one hundred students. She then founded the Associação Cigana Capoeira, where around twenty instructors graduated. She has a degree in Physical Education, Pedagogy and Philosophy from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. Today her priority is teaching capoeira, which she does in schools and other places.

Mestra Janja

Rosângela Costa Araújo, known today as Mestra Janja, was born in 1959 in the city of Salvador (BA). As she says in an interview given to Almanaque Brasil in 2018, she had never thought of practicing capoeira during her adolescence. This was because her maternal family, made up of white people, demonstrated no connection to Afro-Brazilian culture.

In 1983, she started training with Grupo de Capoeira Angola Pelourinho-GCAP, in Salvador, a reference point in the promotion of Capoeira Angola in Brazil and abroad, and directed by Mestre Moraes. It was there that she found something she had always been looking for: to think, about the body and historical identity from the perspective of African culture.

The Nzinga de Capoeira Angola Group was born in 1995, when Janja moved from her hometown – where she had graduated in History from the Federal University of Bahia – to São Paulo, where she did her Master’s and her Doctorate at the Faculty of Education at the University of São Paulo. In the 1990s, , Paula Barreto (now Mestra Paulinha) and Paulo Barreto (now Mestre Poloca), which were part of the GCAP (Grupo Capoeira Angola Pelourinho) in Salvador since its foundation, joined the Nzinga Group. The group’s website states:

The Nzinga Group focuses on preserving the values and foundations of Capoeira Angola, according to the lineage of its greatest champion: Mestre Pastinha […] (1889-1981) […] Its principles are the fight against oppression , the preservation of values that we inherit from the African diaspora, and caring for children and young people, mainly through culture and education. This includes the fight against racism and against gender discrimination.”

Gradually, Nzinga became a reference point in the struggle for women’s equal rights, inside and outside the rodas. The group has just published a manifesto against machismo in capoeira, in which it ensures:

Our solidarity is with ALL capoeiristas who are victims of violence, we work towards men practicing violence taking responsibility for their actions, and for a world and a capoeira in which we are all truly free. (Note from Grupo Nzinga de Capoeira for the end of gender violence,” 2020).

In 2004, Mestra Janja received the title of Paulistana Citizen, granted by the City Council of São Paulo, for her important role in fighting for and preserving the values of the black community. In 2013, she was also awarded the title of Bahian Citizen, granted by the Salvador City Council.

Today, Mestra Janja is a professor in the Department of Gender and Feminism Studies / DEGF at the Federal University of Bahia. On March 8th (International Women’s Day) 2020, the Nzinga Group celebrated its 25th anniversary and commemorated their achievements and their work in five Brazilian cities and twelve cities abroad.

Other iniciatives

Another achievement towards women’s empowerment was the creation of groups formed by women, such as Mulher & Capoeira, Obirimbau – Berimbau Feminino and the Mulher-Capoeira Movement, which I am part of. We formed it in Piracicaba in early 2018 and its participants are capoeiristas (among them, contra-mestres and teachers from different capoeira groups in the city, as well as researchers) who, through sharing knowledge and experiences, seek to strengthen women’s representation in capoeira.

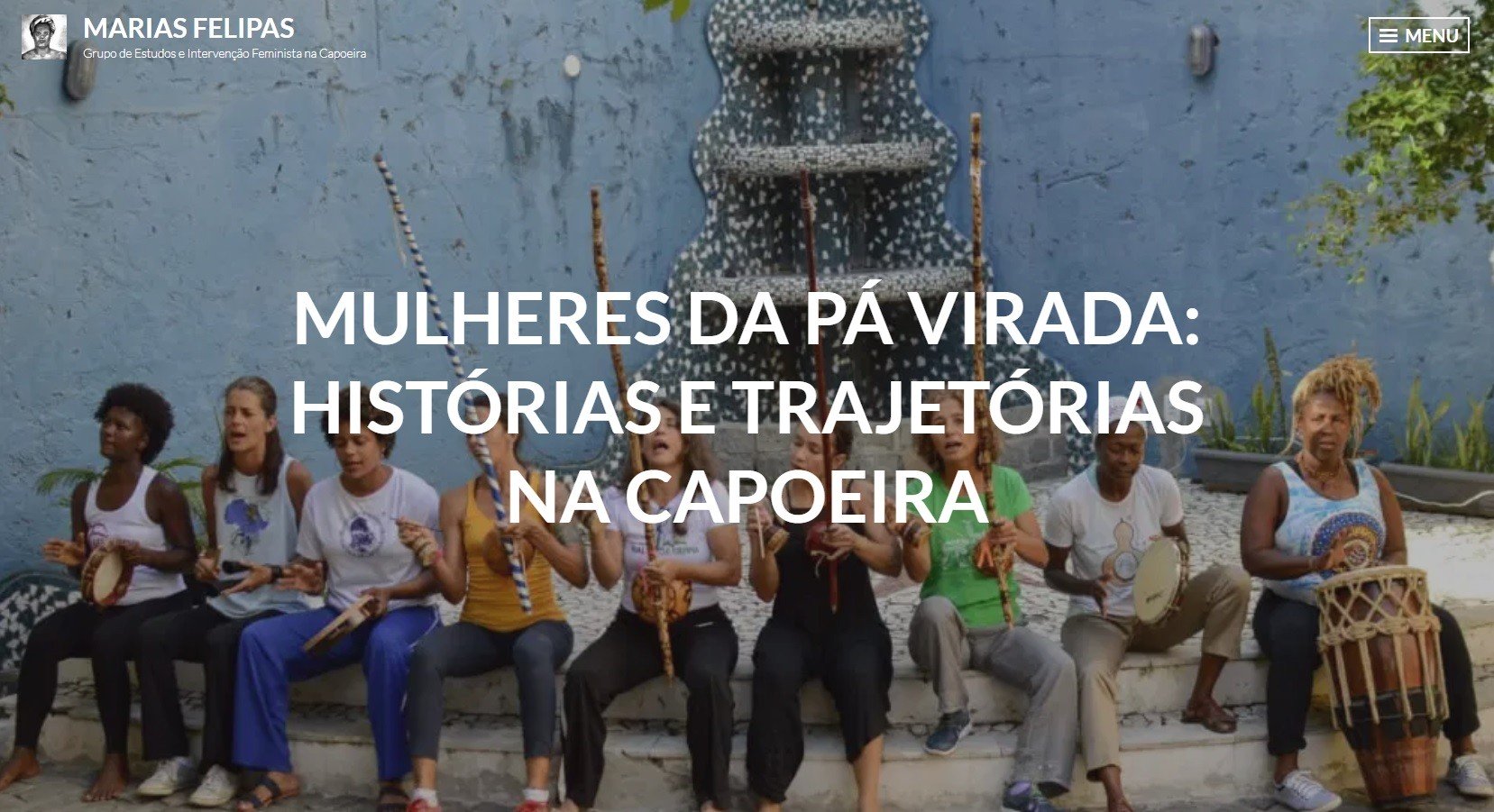

The Collective of Studies and Musical Interventions Marias Felipas is made up of female capoeiristas, researchers, educators and activists. On July 20th, 2019, it launched the Documentary Mulheres da Pá Virada in Salvador (BA). From my perspective, this documentary is a compelling record of female capoeiristas from different generations.

Final considerations

Here, I make the words of Grupo Nzinga de Capoeira Angola my own, which state that:

Using capoeira as a space for political discussion, we introduce questions about the need for shifting roles and values [created in a context marked by different types of violence].” (Note from Grupo Nzinga de Capoeira for the end of gender violence, 2020).

The presence of women in capoeira may promote new paradigms in this art form, as it starts from another social space – one affected by violence – within a society marked by machismo, and, this can never be said enough times, by racism too.

I think it is thus essential for male capoeiristas – regardless of their group, style and graduation – to rethink their masculinity and responsibility in this fight for equal opportunities for both sexes in the capoeira community.

Since the 1980s, capoeira masters and researchers have been publishing books, doctoral theses, master’s dissertations and articles which work to further expand the theme of capoeira and gender. By the way, I consider that the documentary Mulheres da Pá Virada is very important, since, in an unprecedented way, it retraces the trajectory of some of the most renowned Capoeira Angola Masters of Brazil of different generations.

I believe that this contributes not only to the singular perception of the female body in capoeira but also to the conquest of the legitimacy of the female space and its manifestations in the capoeira roda and the circle of life.

References

Books

LIMA, Correia Lucia. Mandinga em Manhattan: internacionalização da capoeira. Rio de Janeiro: MC&G; Salvador: Fundação Gregório Matos, 2016.

PIRES, Antonio Liberac Cardoso Simões. A capoeira na Bahia de Todos os Santos: um estudo sobre cultura e classes trabalhadoras (1890-1937). Tocantins/Goiânia: NEAB/Grafset, 2004.

______. Culturas Circulares: a formação histórica da capoeira contemporânea no Rio de Janeiro. Curitiba: Editora Progressiva/Salvador: Fundação Jair Moura, 2010.

REIS, Letícia Vidor de Sousa. A capoeira no Brasil: o mundo de pernas para o ar. 3ª ed. Curitiba: CRV, 2010.

ZONZON, Christine Nicole. Nas rodas da capoeira e da vida: corpo, experiência e tradição. Salvador: EDUFBA, 2017.

Sites

Disponível em: https://portalcapoeira.com/capoeira/capoeira-mulheres/mulheres-da-pa-virada/ Acesso em: 18 dez 2019.

Disponível em: https://portalcapoeira.com/capoeira/capoeira-mulheres/documentario-sobre-mestra-cigana/ Acesso em 03 mar. 2020

Disponível em: https://www.geledes.org.br/as-varias-faces-da-violencia-contra-as-mulheres/ Acesso em 05 mar. 2020

Disponível em: https://almanaquebrasil.com.br/2018/01/31/mestra-janja-se-penso-na-africa-estranho-menos-a-presenca-da-mulher-na-capo Acesso em: 05 mar.2020

Disponível em: http://mundoafro.atarde.uol.com.br/ Acesso em: 05 mar. 2020

Disponível em: http://nzinga.org.br/pt-br/grupo_nzinga Acesso em: 05 mar. 2020

Disponível em: http://mulheresnoaikido.blogspot.com/2016/06/serie-as-mestras-das-artes-marciais.html Acesso em: 05 mar. 2020

Disponível em: https://www.facebook.com/grupo.nzinga.5/photos/pb.629045683815350.-2207520000../2786655948054302/?type=3&theater Acesso em: 17 mar. 2020

Disponível em: https://www.jornalterceiravia.com.br/2019/05/01/mulheres-da-capoeira-discutem-assedio-em-campos/ Acesso em 09 mar. 2020