By Filipe Amado.

Beginning in 1920, there was a significant change in the way capoeira was referred to in the São Paulo newspapers. Following a trend already underway in Rio de Janeiro, with names such as Mello Moraes, Coelho Neto, Anníbal Burlamaqui, known as mestre Zuma, and Agenor Moreira Sampaio, known as Sinhozinho, numerous articles began to appear by intellectuals defending capoeira had to be regulated and methodized, as a genuine national sport.

Doctors, writers, literati, journalists and even diplomats defended capoeira in schools and barracks, with nationalistic speeches, emphasizing its efficiency as a martial art, its physiological benefits, and often stripping away its black and slave ancestry, as if this were a necessary cleansing to make it worthy of exhibition. As an example, the article by Annibal Silveira, still a medical student when he wrote it, who graduated from the University of São Paulo in 1931 and was a professor at that university and lecturer in psychiatric clinics. His article in the Correio Paulistano newspaper, on April 7, 1927, begins like this:

Among the manifestations of voluntary physical work, there is a genuinely Brazilian one. It will not be so because of its dissemination in the country or the prestige it enjoys in national sports circles. But its origin and, above all, the social class that practices it, make it a typically and unmistakably indigenous game. We refer to capoeiragem. However, almost nothing about it has been produced with a scientific view”. (My emphasis)

What first strikes is the origin attributed to capoeira by the doctor: Indigenous! In other words, a total erasure of black identity, its connection with slavery, its past and its present at the time, connected with the popular and especially the blacks, who lived in cities such as São Paulo and used capoeira in their daily lives.

On the streets of São Paulo

In my last article about capoeira on the streets of São Paulo, I pointed out the significant presence of capoeira among the populace, as a black tradition dating back to the 19th century and intensifying in São Paulo during the first decades of the 20th century. Capoeira was present in black communities as a form of recreation, as a means of resolving feuds, conflicts with the police, territorial disputes between groups, workers, women and children. Capoeira was frequently reported as urban violence by newspapers in São Paulo in the police reports, especially in the first two decades of the 20th century.

Another example is an article in the newspaper Diário Nacional, from 1927, entitled “The capoeira game should be part of our physical education; unjustifiable prejudice that exists against it.” Signed by J.C Alves de Lima, who was a Brazilian diplomat in the United States, this article again makes the suggestion that capoeira be adopted as a sport and fight, supported by eugenistic arguments. The article, dated November 6, 1927, ends as follows:

… why not adopt it in our schools during recreation hours? Other peoples of greater physical value can punch themselves at will. Not us. Let’s popularize the game of capoeira, innate of the Brazilian people. That is why no other people will dispute it with us.” (My emphasis)

We need to understand the context of the time to explain this change in the newspapers’ perspective. To begin with, there was a search for a national identity among the intellectual strata, the greatest example of which was the 1922 Week of Modern Art. In this sense, while the Japanese martial arts were spreading around the world, driven by Japan’s victory over Czarist Russia in 1905, Brazil was looking for its martial art that would stand up to the others (ASSUNÇÃO, 2013). Sporting practices, moreover, gained considerable importance in a vision of health that was heavily influenced by eugenics, a pseudo-medical theory that was to inspire fascist and Nazi visions in Europe. Even so, capoeira was still forbidden, and its practice was considered a crime.

The fact is that, spurred on by these apologetic speeches about capoeira in the newspapers, capoeiras began to appear in the São Paulo ring, initially by challenging a supposedly invincible Japanese jiu-jitsu fighter, Geo Omori. We must remember that capoeira in the ring, as well as on the streets, is a phenomenon present and known in other Brazilian cities, such as Rio de Janeiro and Bahia, but hitherto unknown on São Paulo soil.

We shall make reference here to two important fights. In the first, a capoeira man from Rio de Janeiro came to fight on São Paulo soil, probably interested in the prize money and visibility. The fight between Osvaldo Caetano Vasques and Geo Omori is announced by the Diário Nacional, on October 13, 1928, with the expectation of proving “which of the two fights is more efficient.”

Osvaldo Caetano Vasques is a Rio de Janeiro sambista known as Baiaco, from the Estácio group, who together with Ismael Silva founded Deixa Falar, Rio de Janeiro’s first samba school, precisely in 1928. Although Baiaco is known as a samba dancer, and not as a capoeira dancer, we know that he was one of the carioca rogues and, therefore, frequented places where capoeira or the pernada carioca occurred

Without ruling out the probable opportunism of Baiaco, in São Paulo he is effectively presented as a capoeira champion, and his fight with Omori is watched with great expectation by a gigantic audience at the Queirolo circus, in the city centre..

The fight was a disaster and Baiaco’s defeat outraged the newspapers, which claimed that there had been cheating and a set-up, and that the outcome had already been agreed upon before the fight began. Even so, the event opened space for other capoeiras to come forward with less fear of repression against the practice, which until then had been criminalised.

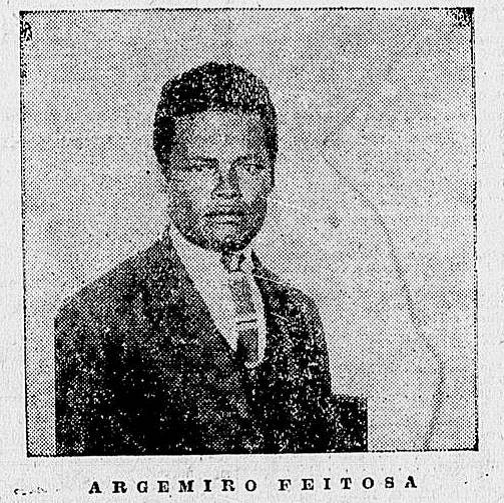

This is the case of Argemiro Feitosa, a native of Ceará who was part of the Brazilian Navy and had been living in São Paulo for seven years. Feitosa commented on Baiaco’s fight in the Diário Nacional newspaper and stated that a capoeira fighter would never lose to a jiu-jitsu fighter. He takes advantage of the opportunity and challenges Geo Omori to a fight. The challenge was promptly accepted. About Baico and Omori’s fight, the newspaper publishes the following commentary by Feitosa on October 21, 1928:

Baiaca (Vasques) started well, giving the initial touch followed by a frontal kick. Defending that attack the Japanese moved away, becoming completely uncovered. This was the perfect time for Baiaca, taking advantage of the impulse of the frontal kick, to make a low sweeping kick, followed by two “stingray tails” (rabo de arraia), falling immediately in the invincible position of the bird jump. Baiaca missed at this moment an excellent opportunity to put his adversary out of the fight. The Japanese intended to throw a few leg kicks by advancing towards Baiaca, threatening savatadas. He remained thus, many times, supported on one foot, completely uncovered, missing many opportunities for the capoeira to take down his adversary, throw a stingray’s tail and other effective blows. Baiaca would have easily dodged Omori’s chases, falling into the “birdie” position. In his neck grab, the Japonez was still uncovered for a sideway kick – a strong blow to the chest produced by the foot.”

His analysis of the fight is a good example to understand how capoeira was practiced in the early 20th century. Numerous kicks and moves are mentioned, some of which are well known and used in capoeira today, such as the “stingray’s tail”. Others ,such as the “invincible position of the birdie jump”, are very difficult to imagine.

Feitosa’s challenge to Omori turns into a great event, much bigger than Baiaco’s fight, and with wide repercussion in the São Paulo newspapers. The newspapers A Gazeta, Diário Nacional, Correio Paulistano, and Estado de São Paulo reported and reviewed the fight, with the Diário Nacional covering it most extensively, with 29 articles about the fight, from October 1928 to January 1929, when the confrontation actually took place.

The editorial staff of the Diário Nacional was extremely supportive of capoeira, publishing articles and encouraging the fights, as a means of demonstrating the superiority of capoeira. In preparation for the fight, Feitosa was interviewed by the newspaper on October 20:

I think that the small centres, where capoeira is now taught on a small scale, should get together and form a large institute, much more efficient in spreading the sport. (…) There are 17 main strikes in capoeira, known by all capoeiras. These are better according to the greater or lesser ability to apply them. They must also make use of many counter-strikes and supplementary movements.”

Feitosa’s accounts to the newspaper are very interesting and reveal facets of capoeira at that time. We can see that there was a structure to the techniques and that, according to Feitosa, there were several teaching centres. Feitosa also states that he intended to publish a book on capoeira and open a school for the sport.

The fight between Feitosa and Omori became a national event, with wide repercussions in the newspapers, which were enthusiastic about capoeira and extremely excited to prove the superiority of the national art over the foreign one. Authorities from various cities attended the event, held at the São Bento football field in January 1929, with a large audience in attendance.

The fight again was a failure and ended with victory for the Japanese in the third round, with the victory described as easy in the periodicals

Feitosa’s defeat was a great frustration to the newspapers and apparently to the public, who were infected by the nationalistic feeling surrounding capoeira and by the magnitude the fight attained. However, to us it shows the paths capoeira took in the early decades of the 20th century, and the dispute that raged over its meaning, its action and its place in bourgeois republican society, eager for national symbols to build a Brazilian identity. The repercussions in the newspapers and the magnitude the fight gained, with a large audience, the presence of authorities and popular clamour, reveal an important chapter on capoeira in São Paulo, a forgotten location within capoeira historiography and which we now discover hosted an important fighting match, where capoeira (not so much Feitosa) was the main star.

Feitosa disappeared from the periodicals and other capoeiras appeared, but without the same impact. Capoeira remained unimportant in São Paulo newspapers until the mid-1930s, when it disappeared for good, only to reappear in 1949, when Mestre Bimba came to São Paulo with his students, visited Kid Jofre’s academy and took part in fights at the Pacaembu stadium.

We know the importance of Mestre Bimba’s fights and victories in consolidating his project of a regional Bahian capoeira, which makes us wonder what capoeira would be like in São Paulo if Feitosa had won his fight, published his book and opened his capoeira school, just like the other capoeiras who appeared discreetly in the news about fights, or did not appear at all.

Capoeira may have disappeared from the rings and newspapers in São Paulo in the 1930s, but it certainly did not disappear from the streets. On the contrary, it continued to evolve and survive, and joined the samba that exploded in the squares, plazas, tenements and basements of São Paulo’s black communities, acquiring new names and musicalities, but retaining its moves and dialectic of meanings: fight and game, play and violence, camaraderie and rivalry, among other polysemies. In São Paulo it became known as tiririca, but this is a subject for our next article.

References:

AMADO, Filipe. Abre a Roda Minha Gente que o Batuque é Diferente, tiririca, capoeira e samba em São Paulo, 1900-1970. Dissertação de mestrado, Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros (IEB) USP, 2021.

ASSUNÇÃO, Matthias Röhrig. Ringue ou Academia? A Emergência dos Estilos Modernos da Capoeira e seu Contexto Global. Rio de Janeiro, 2013. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/hcsm.

CUNHA, Maria Clementina Pereira. “Não me Ponha no Xadrez com esse Malandrão.” Conflitos e Identidades entre Sambistas no Rio de Janeiro do Início do Século XX. Revista Afro-Ásia, 38 (2008), 179-210.

SERAFIM, Jhonata Goulart e AZEREDO, Jeferson Luiz de. A (des) Criminalização da Cultura Negra nos Códigos de 1890 e 1940. Amicus Curiae V.6, N.6 (2009), 2011

Sources:

Correio Paulistano, 7th April 1927

Diário Nacional, 6th November 1927

Diário Nacional, 13th October 1928

Diário Nacional, 21st October 1928

Diário Nacional, 6th November 1927

Diário Nacional, 19th October 1928

Diário Nacional, 13td January 1929

Filipe Amado Filipe Amado is historian (FFLCH USP) with a master’s degree in Brazilian studies (IEB USP) with a dissertation on capoeira, tiririca and samba in São Paulo. He is a capoeira teacher in the Projeto Liberdade Capoeira group, drum master in the Cordão Carnavalesco Kolombolo Diá Piratininga and history teacher in the São Paulo public school system. Researcher and lecturer on the history of capoeira, he has a youtube channel on the subject.